"The Post-Keynesian Worldview in Five Principles"

a talk I gave for the Berggruen Institute on zoom

So, I gave a kind of “what is postkeynesianism” as a lunchtime seminar for the Berggruen Institute’s Future of Capitalism working group. The goal was to have it be something that could be understood conceptually and intuitively as a political-economic approach, rather than an actual explication of research method. So, much of this 101 is vague, and much of it is dedicated to why pk theory is important and relevant, rather than “how to do pk theory.” I think ideally the relation this has to methodology is the relation “genealogy” has to history.

Since the pandemic, I’ve gotten out of practice giving extemporaneous speeches based on powerpoints the way I like to, so I had to actually write down what I was going to say. I figured since it was already written up, why not post it on the substack and get some more circulation going before Berggruen puts up a video of the session. Plus some folks would rather read than listen, I’m this way for sure.

It’s only very minimally edited, and I imagine that a lot of you are likely familiar with most of this, but I think it makes a good 101 that you can share with your friends or the confused. I do kindof feel like if I followed up all the leads in this, and added a few more sections, it would work well as a 100-page Zero Books type “Post-Keynesianism for Non-Economists.” Maybe something to do when there’s a break from “holy shit the pandemic means fiscal policy is back on the menu, everyone get your proposals in right now we’re going to hit 6% GDP growth.”

Here’s the talk:

The first question right off the bat, because I’m assuming everyone is probably unfamiliar, is what is Post-Keynesianism?

Keynes publishes the General Theory in 1936, and makes “macroeconomics” legible as an independent field. Before that there had been various approaches to “economics,” but there wasn’t as clear of a distinction between the economy as a whole, and the individual economic decisions of individuals.

American macroeconomists, for a variety of reasons, took from Keynes the most they could without seriously challenging any of their underlying theories. The trouble here is they basically added a macro overlay that said “sometimes depressions happen for irrational reasons, due to maybe sticky prices or something, and the government needs to cut taxes or spend money to get out of it” while keeping the entire rest of the theory the same.

These folks were called the “neoclassical synthesis” around their time, and eventually become the folks we know as “new Keynesians” today, people like Larry Summers, Greg Mankiw, and Brad Delong. They see the economy as basically efficient, aside from the times when reality throws some sand into the gears of the economic system. So most of the time things are fine, but every now and again the government may have to step in to pull the economy out of recession. The “basically-correct prior theory” that the “neoclassical synthesis” and “new Keynesians” hung onto says that most markets are perfectly competitive, and the labor market always clears, so that there’s never involuntary unemployment. Anyone who’s unemployed more or less deserves it, on this theory, because the wage they would receive would be worth more than the amount they contribute to the production process. While recent developments have added a bunch of individual nuances and mathematical complexity to this account, the core remains the same

Post-Keynesians are folks who instead took the General Theory seriously as a methodological starting point, rather than an unfortunate imposition with some usable policy implications that needed to be merged with a basically-correct prior theory. What Post-Keynesianism is matters today, because it’s seeing a resurgence for a number of reasons.

Financial markets love it, because it does a good job explaining how the economy runs, which is helpful if your paycheck depends on understanding the economy. It gives good causal heuristics for understanding the impact of financial flows on production, and on the economy at large. It also counsels realism about the impact of government policy on economic outcomes. Public debt and private debt are different, the money supply doesn’t cause inflation, private debt does eventually have to roll over, and will have real impacts if it doesn’t.

It’s critical to start thinking about for public policy as well, because the regime of monetary dominance is clearly ending. The past 40 years saw policymakers attempting to do most economic management by doing little more than moving around interest rates and removing regulations. The investment gains from low interest rates alone have largely been exhausted, and we need to in turn move on from the intellectual edifice that focused on them. Fiscal policy is coming back, and its more important than ever to have a clear framework for understanding its impact, possibilities, and limitations.

Also on the policy front, Post-Keynesian economics help us make operational the insights of Modern Monetary Theory. MMT originally grew out of the post-keynesian research agenda, and much of its underlying economic model is still very post-keynesian in structure. I won’t be going too far into MMT, because it has seen a lot more public press lately than post-keynesian economics has. As a whole, I’m strongly supportive and have spent a lot of time in that milieu and it is undeniable that they have had a tremendous positive influence on the public discourse around deficits and public spending.

The covid pandemic has also, inadvertently, shown how powerful demand-side intervention can be. The superdole and other programs kept consumer spending up against a steep decline in hours worked while inflation and interest rates both fell against massive expansions in public debt. Post-Keynesian economics provides a frame where that is an obvious answer in a pandemic, rather than a surprising paradox.

Last, if we’re going to ever actually deal with climate change, we are going to need to dramatically rework our understanding of the economic aspects of a response. Current mainstream models like Bill Nordhaus’s DICE model and degrowth-oriented approaches alike share the belief that more investment today means less consumption today. They try to balance a policy response in light of that view, and come up with solutions that are either ineffectively lax, or politically impossible because of their stringency. A post-keynesian frame shows why a huge investment buildout in climate adaptation and mitigation will actually create an economic boom that increases consumption and compresses wages upwards, provided it is prosecuted in the correct manner. The post-keynesian world is only zero-sum in competition, not in production.

Now, to the title of the talk: the post-keynesian worldview in five principles. It’s safe to assume that economics is basically always political economy, whether it admits to it or not. Political economy in turn always has a particular worldview that its precepts, laws and observations are in dialectic with. Today, we are going to talk about the worldview that most makes sense when thinking about the possibilities produced by post-keynesian macroeconomics as a social technology for understanding the economy, and as a knowledge-generating project.

These five principles are as follows: Quantify the Quantifiable, Everything is Expectation, The World is Downstream of the Provision of Investment Goods, Markets are Sites of Market Governance, and Microeconomic Morals Don’t Match Macroeconomic Outcomes.

Quantify the Quantifiable

What we call the economy is really just a bunch of objects and activities out there in the world. We cut these objects and activities up in a particular way that we think of as “economic” in order to direct them to particular ends, or to understand why some things happen instead of others.

The trouble is, measurement is fundamentally theory-laden. That is to say, when you decide to start measuring the economy, you first have an idea of what it is you’re measuring, in order to pick it out from the stream of consciousness as a particular thing.

Now, mainstream economics structures the economy in a way that involves a lot of unobservable, unmeasurable, or subjective variables. Their basic story is that consumers have preferences. These preferences are chosen to maximize their own utility. Then, these consumers decide how much to work and what to buy based on these preferences. Since different people have different preferences, the choice of what to buy and how much to work moves relative prices and wages around in the marketplace. Eventually, everyone’s preferences are incorporated into the sales price of goods, and the economy approaches an equilibrium where no one can be made better off by trading something with someone else. This price movement then induces changes in the productive structure of the economy, such that the correct amount of each thing is produced to match up with consumers’ preference sets. They explain this whole process as “allocating scarce resources to their most efficient ends.”

On this vision, the goal of the market is to produce a set of relative prices that maximize everyone’s utility, and then for firms to maximize profits against those prices.

While there are a whole lot of problems involved in this story, there are only two we’re going to talk about today. The first is that things happen in time, and so there’s never any point where equilibrium is obtained. We’ll talk about this in more depth when we get to the next principle, that everything is expectation. The bigger problem is that trying to use this story to structure policy or use data to think about economic problems is basically useless.

Most of your important variables on the micro level are totally unobservable. We never see “utility” or “preferences,” and no business goes around measuring the exact “marginal productivity” of each worker it hires so as to decide on their wages. If we want to try to measure these using available data, all sorts of other causal aspects get bundled together such that there’s no reason to think the mainstream economic story is the primary driver.

At the macro level, things are just as bad: there’s no long-run coherent way to measure the natural rate of unemployment, the neutral rate of interest, or real GDP. You get quantitatively messy proxies that are fragile in their methodological specification, and then treat them like rigorously derived quantities. The goal then becomes to attempt to manage the economy by steering around using these unobservable quantities.

In a way, it feels as though they think the difficult task for theory is to provide a complete account of how things ought to be, while describing how things are is fundamentally easy. It makes for easy political prescriptions also. In introductory economics courses, these highly abstracted models founded on unobservable variables are put forward as the platonic ideals that actually existing markets only contingently replicate. The logical policy goal that comes out of this worldview is to try to make all markets more like those of theory.

Post-keynesians instead start from Keynes’ example. In the General Theory, he establishes that there are two quantities that represent real, virtual, actual, and empirical numeraires for the economy as a whole: Labor and Money. Labor he measures as labor-hours in a neat way by assigning all variability to the capital stock instead of to labor.

Different workers don’t have different productivities that they then bargain wages to match, instead, everyone works a number of hours, and each capital good has a different “ability to be worked by this particular worker” that absorbs productivity differences. This is a neat exercise, but since we’re not really doing capital theory today, we’re going to focus on Money as the other numeraire.

In a capitalist economy, production is undertaken for profit and not for use. As such, value is usually measured using the social convention of accounting. Production happens in anticipation of flows of money, just the same as investment and consumption. On this view, things are worth their book value, more or less, and economic actors act based on these book values. What the post-keynesians think is that this represents a good starting point for economic theorizing, to use the quantities that the actors themselves use.

Ultimately, this leads to a balance sheet based view of the economy as a whole. Individual actors have assets and liabilities, incomes and expenditures. Someone’s asset is someone else’s liability, and vice versa. Everything is interrelated through the use of these conventions.

Most participants in a capitalist economy are just trying to keep going, from day to day and month to month. This means meeting their payment commitments, whether they are a firm paying loans, or a household buying food to eat. To meet these commitments requires more than just solvency, in fact it might not even require solvency, it just requires liquidity. Liquidity, in turn, is measured in dollars that are available on hand to meet payment requirements.

On this view, the study of the economy is about studying the flow of payments and the accumulation of assets, not the allocation of scarce resources to their most efficient ends. One of the main benefits this approach has is that it rules out some impossible outcomes: not everyone can run a trade surplus, if there’s a trade deficit, either the private sector or the public sector has to run a deficit to finance it.

The other main benefit is that the data that actors make decisions about is at least in principle available to economists. Anything economically meaningful shows up as a change in a set of flows, or a change in asset values somewhere in the system. These are measurable, and certain regularities can be identified and understood, at least relative to the particular institutional setup at the time. As far as epistemologies go, this is pretty good.

However, it sharply limits the range of valid economic questions. If you’re studying things in terms of payment flows and asset values, there’s no way to do a lot of the kinds of Freakonomics stuff that’s been really popular for a long time. Personally, I see this as a feature and not a bug. The legacy of Gary Becker and economics imperialism is not one that it is worth sacrificing empiricality to retain, but that’s just me.

Everything is Expectations

Our next principle is that everything is expectation. This might sound a little new age-y, and a little “things are what you make of them,” it actually represents a pretty rigorous way of thinking about economic decisions and outcomes.

Expectations inform actions, and these actions in turn create reality. Maybe the simplest model of the Keynesian causal cycle is to say that expected demand drives investment, investment drives employment, employment drives wages, wages drive consumption, consumption drives demand, and demand validates investment.

Now, that’s a little bit of a tongue-twister, but it’s a story of how good expectations create self-fulfilling prophecies, while bad expectations do the same in the opposite direction. Let’s talk about each step in that story:

Expected demand drives investment, because businesses only invest in added capacity or hiring more workers when they think that more people will want to buy their product in the future than do at the present moment. If they expected the same demand, or less, there would be no need to invest at all. They could keep running the same equipment.

Investment drives employment because investment involves purchasing newly-made capital goods. Someone has to build these capital goods, so an increase in investment leads to an increase in employment.

Employment drives wages in two ways. In the first, hiring more people means the total amount paid in wages to the economy as a whole goes up, even if the wage rate stays the same. In the second, an increase in the level of employment tends to increase wages. Firms have to compete for workers, and one way they do is on wages. So far, an increase in expected demand leads to an increase in wages.

An increase in wages then drives an increase in consumption. When wages go up, some portion of it is saved, but the rest is spent on more stuff. Some portion of that money even gets spent on products made by the company that originally invested on an expected increase in demand for their products.

At this point the loop is closed: the expectation of an increase in demand has created an increase in demand. Now, there’s no guarantee that this will be true for every single firm, but it will be true in aggregate. The thing is, this can run the opposite direction just as easily, with everyone expecting worse outcomes at every point, and thus creating those worse outcomes. This same structure animates the study of financial and economic bubbles.

Hyman Minsky talks about this extensively: if you think an asset’s price is going to skyrocket, you start buying it to make a profit. You can even borrow money against it, and use that money to buy more. As the price goes up, the amount you can borrow against goes up as well, and the price starts flying. The whole Gamestop episode last month was a version of this that used call options rather than margin loans, but the principle is similar.

The problem comes for Minsky when the borrowing gets cut off: there’s nothing to support the prices and everything crashes down. Sometimes the operation of extreme expectations can create wackiness in financial markets that can have dire consequences for the economy at large.

But bubbles are neither all bad, nor particularly rare, nor always world-ending in the way the 2008 crash was. The development of new techniques of production and new technologies always requires a bunch of loss-leading expenditure on capital development and R&D. In a purely rational market, these money-losing ventures would never get these, and whatever new developments were possible would be missed out on.

One way of getting a lot of capital to invest in something money-losing is to start something of a bubble in it – to assert that in a year’s time the value of whatever assets are in this sector will have doubled or tripled. If companies in the sector take on that cash inflow to invest in unprofitable new techniques at the technological frontier, those investments may end up paying off farther down the line. Lots of necessary capital structure was unprofitable at the time – think about the giant railroad bubble in the 1870s that gave us the US railways system, or the telecom bubble in the 1990s that collapsed but still produced the material infrastructure for today’s internet.

The principle is something like a line from Tengen Toppa Gurren Lagann: “Believe in the you that believes in me.” Bubbles drive capital investment that might not pay off for thirty years, but the payoff ends up being substantial, and would never have come without the money-losing in the run-up. This seems wasteful if you think the goal of the economy is the most efficient allocation of scarce resources. If you think the goal of the economy is full employment and the full development of the capital stock, then this waste is just an up-front price for a long-run benefit.

[editors note: someday I will actually write my piece on Puella Magi Madoka Magica, Bill Janeway, and Georges Bataille, called, tentatively, “Waste, For Lack of a Better Word, Is Good.” But not today.]

The World is Downstream of the Provision of Investment Goods

This principle more or less builds on the story we’ve told about how everything is expectation.

Demand creates supply, by driving investment. Investment then creates both savings and the capital stock while the capital stock in turn creates resources. That demand creates supply is something I mentioned above when talking about expectation. The first interesting part here is the fact that investment creates savings at the same time as it generates the capital stock, rather than the capital stock being made of past savings.

This is at odds with moral commonplaces, and at odds with both Ricardian or Marxian economics as well as neoclassical or general equilibrium economics. In all of those approaches, savings are necessary to create investment. In fact, Keynes very famously cites the “Fable of the Bees” in the General Theory. As quickly as possible, the fable tells the story of a community that outlaws luxury, and finds itself much poorer now that everyone who used to work in luxury production is out of work.

In the Ricardian story, which is still used today by Marxists and Austrians, the main fund for investment is savings. The assumption is that the economy has a maximum capacity that it is usually running at, and that whatever is not consumed in a given period is saved. In order to invest, savings have to come first, so ipso facto consumption has to be curtailed in order to increase investment.

Neoclassical and general equilibrium stories come to the same conclusion, but through a slightly loopier model that passes through the banking system. They extrapolate out from the idea of fractional reserve banking to thinking that there is a maximum amount that banks can lend that is a function of the amount of deposits that banks have on hand.

In the post-keynesian system, investment doesn’t come out of past savings, and in fact creates new savings. I mentioned before how investment increases wages and employment, and some of the increase in wages is spent on consumption. Well, whatever was saved came into being as a consequence of new spending on the capital goods that created the employment in the first place. It’s hard to imagine initially, but new spending created by investment circulates through the economy as consumption and savings until the entire amount is eventually saved by some collection of people. On its own, this creates a completely different moral story. Consumption, not savings, drives investment and helps society prepare for the future.

This change in the capital stock also changes what is available in the world as a resource. This might sound strange, given that consumption and investment both use up resources, but what counts as an economic resource is defined entirely internally to the present capital stock. Think about crude oil in 1500. It’s not a resource yet, it’s just part of nature. Even if it was found and bottled up, there were no refineries to produce gasoline, nor cars to use gasoline. It wasn’t until enough investment and innovation had happened that that particular part of nature became a resource.

The same thing happens in reverse as well, until the 20th century, whale oil was a critical resource for lubricating early industrial machinery. However, as better lubricants were invented, and investments in electric lighting systems were made, whale oil passed out of “resource” status, and just became part of nature again.

Changing the capital stock changes the stock of resources. Scarcity is only ever an issue for periods of time when capacity can’t change. On a long enough timescale, it is possible to invest around resource scarcity and bottlenecks.

A sort of corollary to this idea is that a change in technology – considered as a change in technique of production, or the social technology of management – has to, at some point, pass through changes in the capital stock. This is more like Clayton Christensen’ “disruptive innovation” than it is Josef Schumpeter’s “creative destruction” because disruptive innovation is so disruptive because it reroutes supply chains and introduces different steps into the production process. At the same time, the kinds of supply chain monitoring techniques that characterize approaches like Just-in-Time manufacturing require a completely different set of capital goods than earlier approaches to mass production.

To really change the technology of production, old capital goods have to be scrapped and new ones brought in. this is different from the mainstream or Solow-style approach to technological change, which sees it as an increase in the value of output that is not reducible to an increase in the value of the capital stock or the value of labor expended.

All of this has particular relevance to the problem of climate change, in two ways. The first is that confronting and adapting to climate change is actually an expansionary economic position, rather than a contractionary one. Any serious investment couldn’t help but be experienced as a boom. As I’ve said a number of times so far, an increase in investment produces more consumption and thus more investment. A build out of the scale needed to adapt our world to the coming rigors of climate change will be so large that it will likely entail full employment and significant investment planning to avoid running into bottlenecks. As an almost accidental afterthought, doing this will compress wage incomes upwards and increase consumption. It’s worth remembering that steel production actually increased after world war two-era production coordination ended, in order to meet the needs of consumers. A boom begets a boom.

The second is that we can use fewer of our actually scarce, or harmful, resources by pursuing investment strategies that route around those resources. The goal is to build out so extensively that most of the dirtiest forms of energy are no longer as necessary as they presently are. While again, this will take a lot, it is doable and doable entirely through an increase in investment without curtailing present consumption. My understanding is that it is much easier to sell an intentional economic boom politically than it is to sell an intentional economic slump.

Markets are Sites of Market Governance

Our next principle should be, I think, one of the least radical, but it is one that doesn’t get made often enough. It is that markets are sites of market governance. There is a very tired critique of market-based worldviews that makes a big deal out of the fact that markets are in fact not naturally arising, and require a strong state to keep them coherent. This is obviously true, but it’s not particularly informative about the role that markets actually play.

Rather than a single autonomous entity, a market is instead where a number of competing administrative entities – something like Private Governments, per Elizabeth Anderson – meet to coordinate their production. These entities can be firms, or households, or regulatory agencies, or industry groups. All of them seek to govern their environment, to convert flux into dependable inputs and outputs. Older approaches that seek to compress this to “price signals” alone that are determined by “supply and demand” are going to miss most of the important detail.

Production is itself a kind of politics, with a wide array of actors and a wide variety of goals. Insofar as the goal of institution-building is to avoid a libertarian or Hobbesian war of all against all, the goal of market governance is to avoid destructive price wars and undue financial losses across the board.

Now, there’s no reason to think of this as democratic in any meaningful way, the way that certain advocates claim. It’s hard to say that it becomes any more democratic when the firms themselves are small, in the manner that Matt Stoller or Louis Brandeis would claim. Many police departments are small, and granted a localized purview, but that does not make them democratic. That firms are constantly and of necessity coordinating does make anti-trust more complex. However, it also makes the idea of economic planning much simpler and much less radical.

The state is just another actor in these markets, albeit a particularly powerful one, given their soft budget constraints and large armies.

In one way, this is an elaboration of the John Kenneth Galbraith position, that the state is meant to be a “countervailing power” to firms in the market. If they don’t like the social impact of the way private actors are governing markets, they are more or less able to step in and change things. It’s impossible to say that this isn’t legitimate, because the state is one of many actors in the market, but it’s also not particularly radical to say that it is legitimate.

In another though, much of the state’s governance of markets is outsourced to the markets themselves. A particularly piquant example of this is the role of the ISDA – the International Swaps and Derivatives Association – in Katharina Pistor’s book Code of Capital. In her telling, the ISDA propagated law-like requirements for derivatives contracts among its members. No actual laws that matched existed on the books, and this was never really a problem until the laws had to be enforced. When they did, in 2008, the courts had no idea how to evaluate these particular contracts, and so adopted the ISDA’s laws wholesale, as though they were US laws, and effectively ruled on their basis. Everyone, including the government, is involved in governing markets.

Ultimately, there’s no form of market that is somehow fundamental or natural. A market is just an administrative technology that provides actors a place to coordinate. A price signal is just one of many that obtains in a well-functioning market.

Before we move on, it is important to mention that not all forms of government are intentional: macroeconomic conditions do a tremendous amount to govern microeconomic outcomes. I like to compare this to statistical mechanics: macroeconomic variables tell you what all of the microeconomic stories, in aggregate, have to conform to, despite not being able to tell you the location or reasoning of any particular particle in the statistical ensemble.

This bites particularly hard in trade theory. The size of the aggregate markup in the American economy – aggregate profits – is set by macroeconomic sectoral balances. The government deficit, minus net imports, minus net household savings gives us private profits. However, that markup does not apply evenly across the economy. Tradeable goods sectors see a lot of price pressure that prevents the markup from settling in those industries. Thus, the markup has to wind up in non-tradeable goods with low elasticities of substitution. There’s a story you could tell that sees the massive inflation in healthcare, education, and rent in the US as the mechanical consequence of global competition in tradeable goods and a large federal budget deficit. While no one intended for that to be the case, the markup had to settle somewhere, and the markets for education and health care wind up being governed by the exigencies of macroeconomic markups and trade in cheap consumer goods.

From a methodological standpoint, all of this means that permanent economic laws and stable parameters are rare, because they mainly characterize the outcome of quasi-political negotiations over the administration of production and consumption between private and public actors. As such, mechanical claims that increased fiscal deficits lead to inflation, or an increase in wages leads to an increase in unemployment seem deeply strange. Ultimately, the world is one of competitive governance over administration.

Microeconomic Morals Don’t Match Macroeconomic Outcomes

This assumption is critical when trying to describe the world. The idea that there exists a global logic to all of the contingent market governance structures arrived at through the processes above winds up dooming most mainstream analysis, but also most Marxian analysis as well. All structures have a local logic within their neighborhood, which they try to inter-operate with other nearby local logics. When you get a really good aggregative principle together – for example here, accounting – you can chain a whole lot of different local logics together in a way that almost looks like a global logic.

Turns out though, it never is, and things need to be evaluated on the level of scale or abstraction on which they occur. There is no underlying unified “logic” of capitalism, just a number of iterative and competing governance structures. No individual or group behavior is really commensurate with emergent structural behavior. In the same way, no macroeconomic outcome is really able to validate the morals believed to underpin microeconomic behavior. It makes ideas of agency and responsibility a huge muddle, and is part of why saying that the unemployed should simply “learn to code” in an environment of long-term insufficiencies in aggregate demand is so insulting. Their unemployment is overdetermined by the system, if they learn to code, and even if they get a job, that overdetermination doesn’t go away and at best the outcome just moves to someone else. Aggregate-level problems require aggregate-level solutions.

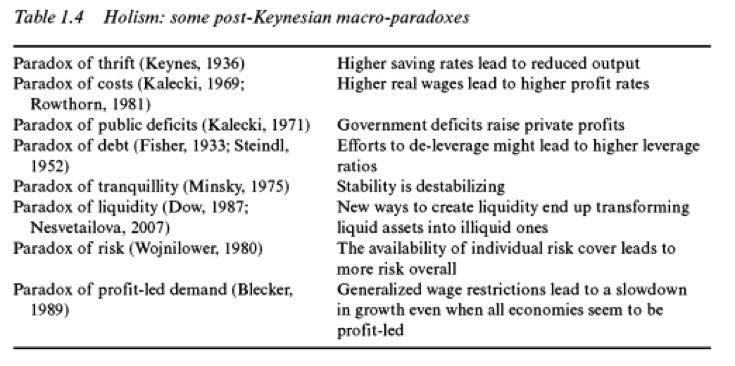

Slightly closer to the ground, we’re going to talk about a handful of well-identified micro-macro paradoxes within the post-keynesian literature. These are helpfully summarized by this table here from Marc Lavoie’s “post Keynesian economics: new foundations.” We’re only going to talk about a few of them though, as we’re getting to the end of our time here.

The original here is Keynes’ Paradox of Thrift. If everyone tries to increase their savings rate, that means they are cutting their consumption rate. If their consumption rate declines, then the incomes of the people selling things to consume falls. Problem is, total output is set by consumption and investment. If investment stays constant and consumption falls, total output falls. The savings rate goes up, but only because everyone is now saving the same amount in dollar terms out of a lower income in dollar terms.

There’s a bit of a moral whiplash here against general exhortations to “save.” How many times have we heard arguments that poor folks need Financial Literacy Training and then they could save more, and wouldn’t be poor anymore. There’s also the old notion that individual savings are what provides funds for entrepreneurs to borrow when investing. Thing is, if everybody started saving more without an increase in investment or in government consumption, it would cut output and throw people out of work. The individual moral imperative that winds up being coherent with a good social outcome is to spend, rather than save.

Kalecki’s paradox of costs looks at the same idea from the firm side, rather than the household side. If employers minimize costs by minimizing wages in aggregate, they wind up cannibalizing the consumption base of the economy as a whole, which eats into profits. If you go the other way, and let wages rise, the rate of profit rises right alongside.

Again, this is a place where the individual demand put on a given company – to maximize profits by cutting wages – doesn’t make sense in the aggregate. For any individual business, traditionally, it’s thought that you’re supposed to squeeze the workers. That’s supposed to be what makes capitalism so efficient, everybody squeezing each other. But if everybody boosts each other, in aggregate, everyone winds up boosted in aggregate, if not in detail.

The paradoxes of debt, tranquility and liquidity described here are all deeply Minskyan. Minsky’s most famous theory was the financial instability hypothesis. [We have talked about that in more detail here.] Basically anything stable - financial products or regulatory regimes - gets innovated around in order to go faster or become riskier or more liquid in search of a bigger payoff. Innovation always happens faster than regulation, so regulation is always backward looking and never finished.

What’s maybe interesting, rather than morally flipped around, is how much of an anti-End of History argument this is. As long as production is monetary and for profit, finance will have some role to play. Finance types constantly innovate, which constantly messes up both their past innovations, and the existing regulatory system. The regulatory systems usually catch on slightly late, once the new financial products have begun to show up and cause problems. So no regulatory system is ever really final, and capitalism is never really solved, the only goal is to move on to the next.

Just Some Last Notes Here

This was a lunchtime seminar with a Q&A after it, so I didn’t write a conclusion. I might go on and develop this into something Bigger later on, but I just thought it might be fun to circulate it in print a little more widely and get some feedback first. It’s not really a history, and it’s not really a methodology, but it’s hard to try to give a framework for a worldview that doesn’t ultimately upset someone included in that worldview. I’d like to minimize that though, so please reach out!

I did have a “Bibliography” slide at the end, which had the following, but feel free to ask for more:

• JM Keynes, General Theory of Employment Interest and Money

• Hyman Minsky, Stabilizing an Unstable Economy

• Hyman Minsky, John Maynard Keynes

• Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie, Monetary Economics

• Marc Lavoie, Post Keynesian Economics: New Foundations

• Frederic S. Lee, A History of Heterodox Economics

• Frederic S. Lee, Post Keynesian Price Theory

• Frederic S. Lee and Tae-Hee Jo, Heterodox Microeconomics

• Jan Kregel, Aspects of a Post-Keynesian Theory of Finance

• Martijn Konings, Capital and Time

• Katharina Pistor, Code of Capital

• Michael Pettis and Matthew C. Klein, Trade Wars Are Class Wars

Wow this was really helpful, thank you.

this is great