Two Ways Of Thinking About The End of the 2010s

literary criticism

Everyone seems upset lately because a lot of things have changed. Change is confusing. Some people are calling it a “vibe shift”. Others might call it “Turning 30”: It’s been right around thirty years since the Cold War really ended and whatever America was born at that ending is now of the age where it has to get its act together and figure out what it’s really doing and why. Even the American most uniquely borne by the Cold War is dead now, not just the era. What was Trump about but burning the last of your twenties on the mania of improper memories with your check-kiting friend whose bar and grill you could still somehow convince yourself wasn’t obviously failing?

Things are different now, and since we’re all good Marxists, we know that that is because of changes in the macroeconomy. But since we’re all also human beings, we know that while statistics might suggest how to operate in situations, they can never really tell you what they mean, either the statistics or the situations. Summarizing Mr. Pound The Learnèd:

“Artists are the antennae of the [I am going specifically against the wishes of that old antique jackass Ezra here when I change the sentiment to] human race; any who neglect the perceptions of their artists decline.”

If you’re looking for meaning, look for meaning where it is. Economic statistics might make a decent lamppost in the markets, but there’s no guarantee that light reaches all the way to meaning. For meaning, I usually turn to poetry. This is mostly chauvinism on my part; verse makes more sense to me more quickly than film or novel or image, and can simply do stranger things.

The goal of this short piece of literary analysis is to make one idea legible in two different ways. Since we’re talking about two different generations of folks — specifically as generations of folks — we should explain things in terms of two generations of poetry, one recognizable to someone about 30 in Cold War America, and one for someone about 30 in Post-Cold-War-America-At-30. For consistency’s sake, I’m also going to try to pick poetry representing a roughly analogous social position across the two time periods, and a roughly analogous artist-audience relationship and rhetorical occasion. Again, we’re trapped by my chauvinism here, but, sadly, as the hammerer would have said to the door were the language different at the time: “Here I stand, I just can’t do no other”.

Let’s take a look at a couple Bruce Springsteen songs, and a song from the Menzingers. Since one of the main themes of the volta under literary analysis is how we have to go back and do things right this time, forgive me if this all points to an even earlier era of literary criticism than was current at the time of the songs themselves, much less now.

Bruce Springsteen

There are two interestingly linked couplets from the songs “Atlantic City” and “The Promised Land”, where the meter and rhyme are such that one could land two different punchlines on the same setup. More simply, you can swap the bolded lines without changing meaning or singability — try it — but when you swap the italicized lines, the songs remain singable but change meaning.

On the left, we see the Koo Problem in full swing. Debts that no honest man can pay — extend and pretend — mortgages or greek sovvies — monetary accommodation insufficient without fiscal air support — everyone who’s already got assets is gonna love specifically the combination of inflation below target and zero rates, not just zero or low rates. And it’s the same for people too: can’t work your way up to a change in asset class without enough demand moving through the system — to say nothing of what happened to the homebuilders — wonder how many folks who built homes in the 2000s got to keep theirs through the 2010s. Just got to gamble — hey, some of the era’s most important growth sectors (like Silicon Valley and Oil & Gas) can look a lot like gambling sometimes, so smile, you’re in good company, It’s Time To Build (tm) — because maybe you can get over that way; who knows what happens to the hindmost but you better believe they’re gonna be stuck with it so they best not be you. A devil to take them is too lavish to even believe in, it’ll probably just be some medical biller in an ashen polo shirt through the phone lines. You can feel it in the ambiguity implied in the relationship too: getting a job and putting money away is for suckers — it’s never gonna work and you just gotta flee while you still can because maybe you can trick the people there this time, not like last time. Everybody knows it’s not gonna work, and if you can make it somehow, you’re safe to just assume every one will stick with you…not go away — and you don’t need to do anything for them because who else are they gonna find who got it working and will deal with their complaining.

On the right we see that things feel, psychically and somatically, worse, but that’s the price of real recovery. It feels bad and you want to explode — everything’s locked up at the damn Walgreens now; what do you mean we have to pay these stupid teenagers sixteen dollars an hour; when did takeout get so expensive what do you mean people have better jobs than delivery boy now — and the dogs on Main Street are howling because they absolutely agree. But they’re only howling; they never bite. Exploding is from weakness — same as biting — if you have to show force there’s no power. Climate change is a real problem, but exploding a pipeline barely produces a halfway decent movie, much less a global solution. It might be that you want to explode and tear this whole town apart, but you know that even if you exploded that wouldn’t happen. There’ll still be things to do afterwards; towns — even previously torn-apart ones like Halifax or Lac Megantic — are resilient because there’s things that need done. Building enough stuff to replace everything built out by folks with big aspirations who didn’t understand how half the systems worked even at the time is hard, and it sucks, but it has to get done.

“It wasn’t easy but we grown men.

I really mean it like the song said.”

Earl Sweatshirt, 100 High Street

One thing to bear in mind for the sake of this analysis though, is that these songs all show up in pretty different contexts. The Menzingers are able to dramatize the tension more clearly by explicitly thematizing it; the construction on Bruce above is totally artificial and even flips the historical timeline. The events that separate optimism and pessimism in the couplets above — rather than “waking up to the last ten years” as we will see in the Menzingers’ case — can be neatly summarized in the figure and actions of one Paul Volcker — another Jersey Boy, but one of distinctly different interests.

The Menzingers

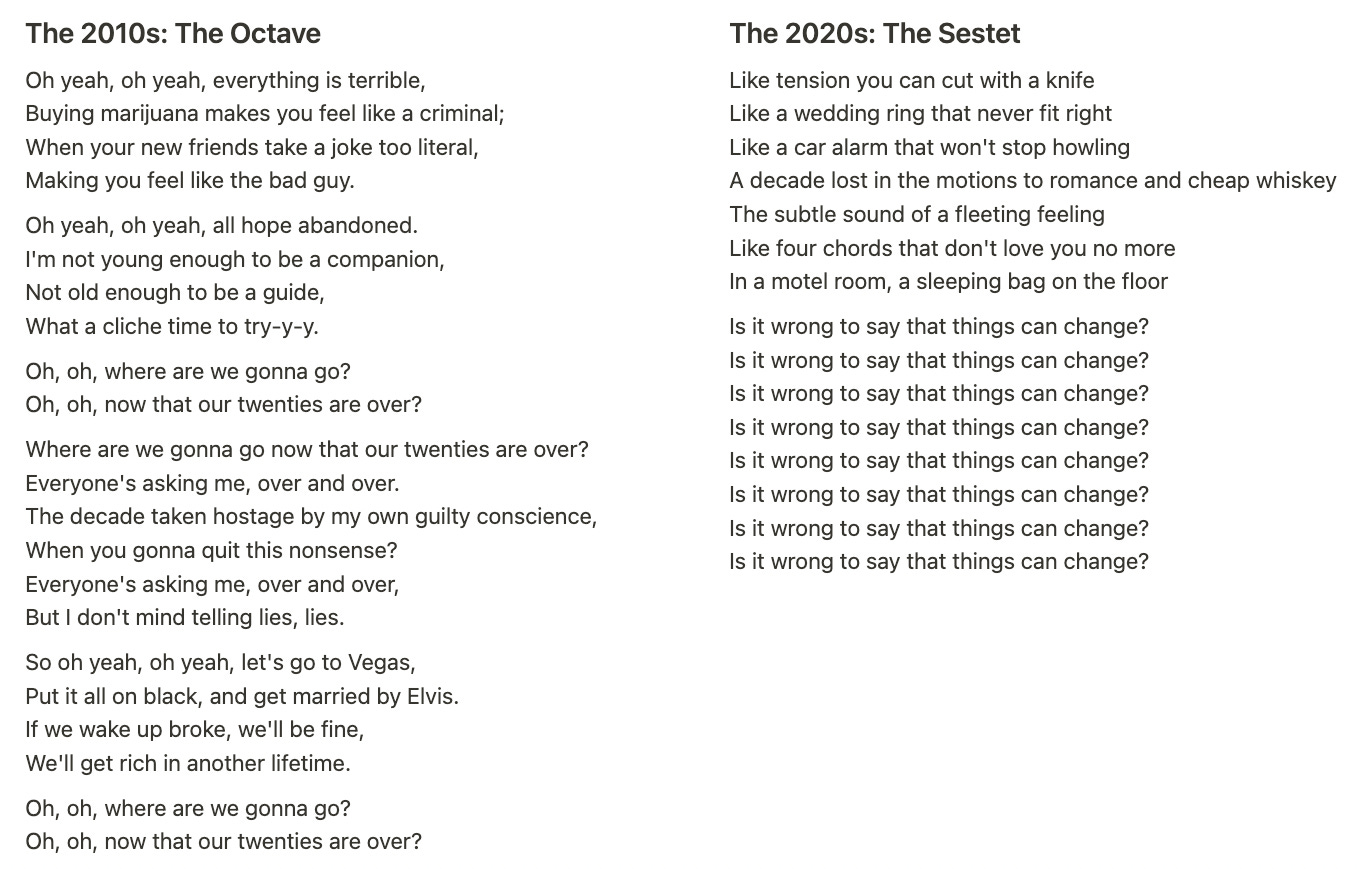

What was unconscious in the Springsteen example by virtue of its artificiality is clear in the Menzingers’ song “Tellin’ Lies”. These are Pennsylvania boys after all, not Jersey — of about the same age as “Post Cold War America” — working out what to do about being how, where and what they are. They are in earnest and they deserve the same treatment as the octave and sestet of sonnets past, with some judicious edits around the level of repetition native to the form of pop punk lyric. Plus, they just make it so easy to do:

I hope you all can understand, because I would find it garish to press the point further.