"The Will To Believe" by William James

What To Do Here If The Truth Is Out There

“But to minds strongly marked by the positive and negative qualities that create severity,—strength of will, conscious rectitude of purpose, narrowness of imagination and intellect, great power of self-control, and a disposition to exert control over others,—prejudices come as the natural food of tendencies which can get no sustenance out of that complex, fragmentary, doubt-provoking knowledge which we call truth. Let a prejudice be bequeathed, carried in the air, adopted by hearsay, caught in through the eye,—however it may come, these minds will give it a habitation; it is something to assert strongly and bravely, something to fill up the void of spontaneous ideas, something to impose on others with the authority of conscious right; it is at once a staff and a baton. Every prejudice that will answer these purposes is self-evident.”

George Elliot, The Mill On The Floss

This section by section analysis of William James’ 1896 talk “Will To Believe” originated in an online reading room. James’ essay is an important analysis of decision making under uncertainty, often caricatured as a license for irrationality. Read carefully, it is something far more powerful: a theory of fixation belief that treats moral risk as epistemically unavoidable and perhaps even desirable.

I want to acknowledge the particular contributions of the users ktb, AmourePrope, Shishi Qivshi, Jason Oakes and Simon for their questions, answers and perspectives. I also want to thank CVAR Editor Alex Williams for his patience and contributions. Statistician Cosma Shalizi inspired some of the basic insights. Others have contributed to this little essay as well. However, I am responsible for any errors in the following.

Contents

Introduction

Who was William James

Precursors

Charles Peirce’s “The Fixation Of Belief”

William Kingdon Clifford’s “The Ethics Of Belief”

Wilfrid Ward’s “The Wish To Believe”

The Will To Believe

Complete essay, section by section

Conclusion

Reactions and Aftermath

Introduction

William James, source

William James was one of the greatest philosophers and psychologists in American history. He had two enormous classics - Principles of Psychology and Varieties of Religious Belief - half of either of which would register their author for immortality. James’ central philosophy of psychology is that the mind or spirit is made of brain. Thus the methods of anatomy (especially neuroanatomy) and physiology are applicable to psychological problems and vice versa. Introspective and behavioristic evidence informs us about neural structure and neural structure underwrites mental and physical behavior.

Today we are reading one of his smaller classics, “The Will To Believe”. This little essay on the process of rigorous belief formation as observed in the human organism illustrates his deep analysis and beautiful style.

But before we start, a bit about James’ writing style. James abounds in paradox, and particularly in long ironic passages where each end balances an over strong conclusion. It makes him a bit windy by modern standards but is enjoyable once you get the rhythm. For example, here is a passage from Varieties Of Religious Experience:

“The next step into mystical states carries us into a realm that public opinion and ethical philosophy have long since branded as pathological, though private practice and certain lyric strains of poetry seem still to bear witness to its ideality. I refer to the consciousness produced by intoxicants and anæsthetics, especially by alcohol. The sway of alcohol over mankind is unquestionably due to its power to stimulate the mystical faculties of human nature, usually crushed to earth by the cold facts and dry criticisms of the sober hour. Sobriety diminishes, discriminates, and says no; drunkenness expands, unites, and says yes. It is in fact the great exciter of the Yes function in man. It brings its votary from the chill periphery of things to the radiant core. It makes him for the moment one with truth. Not through mere perversity do men run after it. To the poor and the unlettered it stands in the place of symphony concerts and of literature; and it is part of the deeper mystery and tragedy of life that whiffs and gleams of something that we immediately recognize as excellent should be vouchsafed to so many of us only in the fleeting earlier phases of what in its totality is so degrading a poisoning. The drunken consciousness is one bit of the mystic consciousness, and our total opinion of it must find its place in our opinion of that larger whole.”

Both the phrase “Sobriety diminishes, discriminates, says no; drunkenness expands, unites, says yes.” and the paraphrase “Alcohol is in its totality so degrading a poison.” fail to capture James’ meaning. Both are necessary to understand the balance of his thinking.

James certainly had straightforward and unironic passions and wrote about them plainly. Particularly, he had a deep rooted hatred of racism and trusts. His vicious description of Theodore Roosevelt could fit John Ganz:

“The worst of our imperialists is that they do not themselves know where sincerity ends and insincerity begins. Their state of consciousness is so new, so mixed of primitively human passions and, in political circles, of calculations; so at variance with former mental habits; and so empty of definite data and contents that they face various ways at once.”

But, by and large, James operates in the world of qualification and shading, a world of delicate and descriptive detail. If someone tells you James’ meaning can be distilled to a simple slogan, they are probably trying to sell you something.

Precursors

Now that we have established who William James was, let’s talk about how he wrote this talk. I decided to take a “genetic” approach, examining him in the light of important precursors. After a lot of thought, I pared down the predecessors to discuss to three essays:

1. Charles Peirce’s “The Fixation Of Belief”

2. William Kingdon Clifford’s “The Ethics Of Belief”

3. Wilfrid Ward’s “The Wish To Believe”

Obviously there are many other influences and inspirations, like George Eliot’s The Mill On The Floss quoted above. Further, it must be remembered that James was what they called a “man of science” first and a “man of letters” second. As we shall see, laboratory practice and discovery is as important an influence on his work here as any “predecessor”.

The first paper up is Peirce’s “Fixation of Belief”, published in 1877. Charles Peirce was one of James’ biggest influences as the two men struggled to plant the seeds of empirical psychology in the rough soil of 19th century America. A bit about who Peirce was in relation to James will help. Best to look at Peirce through the lens of his empirical psychology, as this was their original point of contact. Fortunately, the Peirce-Jastrow result is a classic in the field of the psychology of sensation. Methodologically, it could have been written yesterday with its crystal clear statistical reasoning. The basic conclusion that Peirce makes is that perception is probabilistic and graded in terms of intensity. Following this, Peirce and James saw that the problem of psychology is to ground probabilistic and graded judgements (and psychological behavior generally) in the complex and competing activities of the nervous system.

James was familiar with Peirce’s ideas about the fixation of belief from lectures and discussions long before publication. As we shall see, James draws on Peirce extensively for his anti-Cartesianism, psychological concepts and for the analysis of doubt as a problem with a specific structure. But we will also see that James has many differences from Peirce. Most importantly, James is comfortable with psychologistic language (a person feels doubt) whereas Peirce wants more objectivistic language (a person’s evidential situation is doubtful). It is important to be clear that Peirce’s appeal to an unbounded social process was not merely a regulative ideal. For Peirce, the eventual convergence of inquiry reflects the real metaphysical structure of the world, a post-Hegelian commitment James explicitly resisted.For his part, James’ saw Peirce’s process based objective idealism as leaving the laboratory behind. Wherever you land in this tension, keep in mind that if James’ ever seems to be a bit over psychologizing, it is not accidental. James is not replacing epistemic norms with psychology; he is relocating normativity inside psychological constraints.

We move on to Clifford’s essay. Bill Clifford was a very acclaimed mathematician and physicist who suffered a short and tragic life. Clifford’s work on the algebra of spatial analysis is still a fundamental part of modern algebra and his work on the relation of motion to non Euclidean geometries has been praised as a precursor to relativity. But Clifford was an inveterate workaholic: he would teach and experiment all day and write all night, not sleeping for days on end. As a result of overwork, his health collapsed multiple times, and at the age of 34 he caught a case of tuberculosis that his stress weakened immune system could not defeat.

Tragedy aside, we now move on to the writings. Clifford’s essay “The Ethics Of Belief” is half of a two part series published in 1877 with “The Ethics Of Religion”. Now, “The Ethics Of Religion” is mostly dedicated to anti-ecclesiastical thought. This is not without interest, but “The Ethics Of Belief” is much more interesting. This little essay is a foundational work in what has been called the “agnostic movement” of the late 19th century.

The agnostic movement was a complex and many-sided thing, but all of its protagonists shared the conviction that spiritual life had to be reconciled with modern science. There were atheist-leaning agnostics like William Clifford and belief-leaning agnostics like William James. There were even agnostics named something other than William. The movement was controversial even among non-fundamentalists. Nietzsche contended that the English agnostics replaced religion with an ethic more austere without God than the Christian ethic had been even with God (see his unkind comments about George Elliot for more details).

Clifford’s essay starts by raising the stakes: an example meant to convince the reader that if you have the wrong beliefs then people could die. Clifford’s example is a ship with major flaws that is put out to sea because the owner has convinced himself that the ship must be safe because that’s the only way he can make money off of it. Clifford had just survived a sea wreck so he knew what he was talking about. Clifford’s response to the alleged deadliness of false beliefs is to insist that all our beliefs be founded on something he calls “evidence”. Despite the seeming reasonableness of this requirement, Clifford immediately runs into two problems:

1. Surely the future belongs to those who cry ‘Peace’ when there is no peace?

2. Many of our most important beliefs are founded only on the slim evidence of authority. For example, the evidence that people die when shot by guns I believe on the merest authority.

Clifford’s solution to the first problem is suspension of belief - essentially, choosing to avoid moral risk at all costs. There’s been a lot written on this since 1877: Keynes on validation of investment, Merton in self-fulfilling/negating prophecy, fixed point theorems, Schelling on focal points, the list goes on. James has a sharp thing or two to say about this. As we shall see, James would see Gramsci’s famous phrase “Pessimismo dell’intelligenza, ottimismo della volontà.” as closer to a solution than any kind of ‘suspension’.

Clifford’s answer to the second question is what separates him from a naive evidentialist. Clifford argues that though we may not be able to shake off authority all at once, we can always at least begin the process of inquiry. This is directly related to the James/Peirce pragmatist program. Now, nobody can read Clifford’s essay and think he has answered the issues he brings up. A G K Chesterton could have easily reduced him to ridicule. But he writes with honesty and passion far more powerful than jibes can deflate.

Now to finish with Ward’s 1893 essay, “The Wish To Believe”. Wilfrid Ward was an English Catholic apologist, an influence on G K Chesterton and the other apologists of that generation. The essay is a dialog between largely but not exclusively between two thinly sketched characters, a young agnostic and a Catholic priest. It goes pretty much like you think - the priest offers brilliant answers to all the agnostic’s questions & suggestions. The essay is enlivened more through Ward’s impressive erudition than by surprise.

For our purposes, the important bit comes in the first day of dialog when the priest ‘refutes’ the young agnostic’s objections to the Catholic approach to the evidence for miracles. The agnostic says that the traditional religious person’s attitude toward the evidence for religion is untrustworthy. Why? because the religious are intrinsically biased: they wish to believe the evidence has such-and-such conclusions. The priest then says “Sure but there are two kinds of wishes: Wishes like ‘Loving eyes can never see’ and wishes like what Michael Jordan had to defeat the Pistons. The second kind of wish should increase our respect for the reasoner. Only by such wishes can we be convinced to put forth the effort to gather the evidence of a hypothesis as unlikely as miracles.”.

Ward’s second type of wish is an important point for James, related to the first point that tripped up Clifford. What it highlights is a volitional, effort-taxing aspect fundamental to rigorous belief formation. Hard thinking burns calories and strains the nerves. Thus rigorous belief formation is subject to the same kind of Peirce/Jastrow/James empirical psychology as any other strenuous action. From this insight “The Will To Believe” was born.

The Will To Believe

Introduction

In this section, James is introducing himself to his audience and situating himself in the intellectual world they would know. William James, a good Harvard Man if also a lifelong outsider to all institutions, gently welcomes himself to the “old orthodox College” - i.e. Yale. The orthodoxy that led to the foundation of Yale is Congregationalist Reform Christianity with its sola scriptura and its sola fide.

Moving from the physical location of the lecture, James situated himself in the intellectual world by discussing Leslie Stephen. James had actually met Stephen in 1882 while working on Principles Of Psychology. Leslie Stephen “met” someone else special that year - his daughter Virginia was born that year. Virginia would later cite William James’ concept of “the stream of consciousness” as an important influence on her novels.

But as to why Stephen is quoted here: Leslie Stephen was the social center of the English “agnostic” movement. His essay “An Agnostic’s Apology” is best summarized by this sentence: “We [agnostics] wish for spiritual food, and are to be put off by these ancient mummeries of forgotten dogma.”. Stephen’s name would immediately signal to the audience they are going to hear a work of agnosticism (albeit belief-leaning agnosticism).

James discusses sola fide a bit. This is a central doctrine of large segments of Protestant Christianity. The basic idea is that the Savior sacrificed himself thousands of years ago for you out of sheer personal love (that is, unmerited grace). In some sense and compressing significantly, the point of the imitation of Christ is to recognize oneself as sanctified by the God who always loved you, not to “earn” something. How can you earn an infinite reward anyway? Punning on sola fide, James declares the goal of the essay is justification of faith alone, that in important circumstances the faith in a belief is a sufficient call to hold that belief.

Of course, James’ notion of “belief” is not the same as Martin Luther’s. In James’ concept of “holding a belief”, the belief must be understood in the light of fallibilism. In Quine’s much later phrase, James does not mean believing “hold come what may”.

Now we come to the most important paragraph in the introduction, which guides the whole piece. James says that his analysis will show his iustificatio fidei is “lawful philosophically”. That is: it can be an ordinary part of scientific explanation. In fact, James thinks that all religious experiences, not just the justification of faith, can be examined psychologically (without settling their metaphysical truth). James would bring his idea of the scientific investigation of religious belief to a higher level with his Varieties Of Religious Experience. But here James is only examining this one, admittedly important, part.

James’ idea that faith can be an ordinary part of rigorous belief formation is a provocative thesis. James goes so far to say that all of his students, Christians or atheists, feel that “faith” (i.e. belief that goes beyond justification strictly speaking) is not a part of ordinary scientific thought. But James will have no such nonoverlapping magisteria - he is determined to examine the process of rigorous belief fixation wherever that analysis covers. In the next section, we will start that process.

Section I

In this section, James is introducing a series of conditions to block the method of Cartesian or Hyperbolic Doubt (Peirce’s phrasing). Hyperbolic doubt was, or is held to be by some intellectual historians to have been, the dominant philosophical method of what might be called Idealistic Pre-Critical Modern Philosophy. The basic strategy was to “doubt” all truth until one finds an indubitable non-tautology, then construct all knowledge on top of that. The issue with this form of foundationalism is that doubt is only brought in temporarily, like a vaccine - use a little doubt to extinguish all doubt. Is this the methodologically correct way to use doubt?

Pragmatists think not. The rejection of hyperbolic doubt by Peirce and James is fundamental to the way they see the world. It takes real neural effort to repair what Quine would later call “the web of belief” from doubt, and both reject the idea that such efforts can be avoided by simple words. Thus James introduces three axioms which delimit the actual doubts as experienced by humans from the merely potential doubts examined by Descartes. They are that the doubts must be

Live,

Forced and

Momentous

First, the concept of a “live” doubt. For a doubt to be “live”, the possible beliefs must be contradictory but not decided. James’ axiom of the liveness of a belief is grounded in his psychological research - he knows the attention fixing and reflective association of belief fixation takes energy and effort. Thus he sees a sort of neural “Production Possibilities Frontier” for the production of new ways of thinking. Without a notion like liveness, every belief would have to be treated as perpetually in the process of being doubted, a demand incompatible with finite attention, finite energy and the need for action in real time. James, a fallibalist, thinks every belief can be doubted but not that they always are.

You’ll notice that James defines the “liveness” of an option in a highly subjective way. The liveness of an option is a relation it has with you, not an objective relation the option has with a body of evidence. This was a major source of conflict that James had with Peirce. Peirce wanted to protect objectivity by embedding rigorous belief fixation in an unbounded social process. James felt such infinite processes brought in metaphysics at the wrong level. This is a subtle but real difference. Put another way: James emphasized the subjective sources of knowledge (immediate experience) but Peirce emphasized that sensation becomes knowledge when organized into objectivity (norm-governed inquiry).

The subjectivity of liveness shouldn’t be confused with the liveness of a proposition being a choice. One can no more choose the liveness of a choice than one can choose to not feel the subjective sense experience of pain when touching a hot wire. The liveness of a proposition is directly perceived. Liveness is “felt in the gut”. Liveness is thus subject to the same illusions and faults as any other sensation.

That the choice must be forced has a further target: Captain Kirk and the Kobayashi Maru. The considerations for an analysis of creativity and finding subtle third options are wholly different from the considerations of James’ lecture and thus must be excluded.

Finally, momentousness blocks the attempt to use arbitrary general rules to get out of analyzing the specific proposition. If a decision was not momentous, then one could try to make a rule like “Choose the option which is the least work.” or “Flip a coin.”. These methods are clearly not part of rigorous belief formation.

These are James’ three axioms for a situation in which an organism would bother wasting precious calories changing its mind. It is clear that all three are necessary - negate any one and an easier way of organizing the mind than rigor is possible. Are they sufficient? Later, we will talk about some readers who think they are not. But for now, we will move on to the next section.

Section II

James now moves on to consider what a belief is, grounding in our “volitional and passional nature”. By beliefs which come from our passional nature, James means those beliefs which are cooked up for the stream of consciousness to provide easy flow. Let’s start with an example of a belief grounded in passional nature: imagine coming upon my gazing into the evening sky. You ask me the color of a particular patch of multicolored heaven. You’re shocked that I quickly answered “Red” - that patch was in my blind spot! You ask why I believed it so and I say that I saw it with my own eyes. You direct my attention to the strange green spot in the sky. What happened? In Peirce’s spirit, I in fact (mistakenly) deduced the color of that patch of sky from its presumed continuity with my other sense experience. My answer was swift because I had no conscious feeling of deduction. My brain did that to ease conversation with the illusion of visual continuity. This process is how the greatest mass of our beliefs is formed: our passional nature builds beliefs for the stream of consciousness just in time for their use.

How then does our volitional nature enter? James illustrates the entry place of volition in his magisterial Principles of Psychology with a passage of Leviathan:

“mental discourse, is of two sorts. The first is unguided, without design, and inconstant; wherein there is no passionate thought, to govern and direct those that follow, to itself, as the end and scope of some desire, or other passion.... The second is more constant; as being regulated by some desire and design. For the impression made by such things as we desire, or fear, is strong and permanent, or, if it cease for a time, of quick return: so strong is it, sometimes, as to hinder and break our sleep.”

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, Ch 3 (as quoted in WIlliam James, Principles of Psychology, Chapter XV “Association”, Section 14 “History of the Doctrine of Association”)

James does not agree with all of Hobbes’ ideas, but does take advantage of this insight. What James means by beliefs grounded in volition is those beliefs which have impressed into our patterns of thought through the law of association via repeated experience in voluntary reflection. Consider why a childhood fancy is as clear as day to an old man who cannot remember where he put his keys: the key place was experienced once, the childhood dream experienced over and over again in reflection. So to the belief we once were so critical of is added to our stock of calcified beliefs by repeated internal experience. One can see why James is concerned with the calories the organism spends in impressing a belief via volition!

Because of the expense of volitional reinforcement and the vast quantity of passional belief, one can understand James’ rhetorical question of whether belief formation has any volitional aspect at all. The illusions of blind spot “vision” cannot be willed away. It would be absurd to try to construct the mass of our beliefs through explicit volition, and yet there are cases where volition takes center stage - those covered by James’ axioms.

James starts by discussing Pascal’s Wager. For now, he is highlighting the essentially volitional core. He shows that if such a framework lacks the axioms for belief formation that James outlined earlier (postpone whether it does until later), then Pascal’s argument is unconvincing even if not answered. Such an argument would be subject to symmetry arguments (why be Catholic rather than Protestant, or Muslim or Hindu or Buddhist or …). As we shall see, this is only one phase of James’ dialog with Pascal.

James continues by discussing the agnostic position. Where volition is at the core of Pascal’s model, to the agnostic, “volitional belief” smacks of arbitrariness. He is aware that the nerve of agnosticism cannot be answered by a purely volitional theory. To answer Leslie Stephen’s wish for good spiritual food by telling him he should just enjoy what he has is as crude as it is ineffective.

James lets Pascal stand on its own, but James brings in many agnostics to sharpen their position. He quotes Florence Nightingale associate Arthur Clough. Clough’s poem gives a kind of agnostic creed: “It fortifies my soul to know/that though I perish, truth is so”. This moral fits with Rorty’s analysis that “truth” is a post-Christian substitute for God. James also takes a Thomas Huxley quote from Influence Upon Morality Of A Decline In Religious Belief. Finally, he brings in Clifford’s “The Ethics Of Belief”, which we have already discussed. This shows that James is engaging with agnostics seriously as a group, not just picking on a few poor souls.

Now that James has set up Pascal and the agnostics as his right and left, it remains for him to show that a continuous organism can be built via psychological analysis.

Section III

The basic point of this section is that belief formation is a process. That process involves volition and passion. Indeed “It is only our already dead hypotheses that our willing nature is unable to bring to life again.”. James presages Rorty in saying “Our belief in Truth itself, for instance, that there is a Truth, and that our minds and it are made for each other, what is it but a passionate affirmation of desire, in which our social system backs us up?”.

As a matter of empirical fact, “our non-intellectual nature does influence our convictions.”. James even psychologizes those who would deny it - what is it but Clifford’s passional nature that led to the writing of his wonderful essay? As Schopenhauer put it, man can do what he wills, but he cannot will what he wills.

This part of James’ writing led some to the complaint that his pragmatism is just rehashed utilitarianism. But here James is making an empirical point: that Clifford and Cardinal Newman are both realizations of the belief making process. From James’s perspective, the distinction between evidentialism and the grammar of assent is real but misses the deeper fact that they are both inside the process of belief formation.

James uses telepathy as a deliberately provocative example in this section. He shows that rational agents can refuse to examine evidence although the evidence has not been refuted. Why? Because sometimes accepting the evidence would disrupt their web of beliefs, institutional practices and explanatory norms to a practically intolerable degree.

This can be shown by a less extreme example. Quality engineer W. Edwards Demming asked when we should believe a table is clean. This is not historically arbitrary - Demming was highly influenced by pragmatist C I Lewis. Clearly, the answer to “Is this table clean?” depends on the question “Clean for what purpose?”. Food preparation and chemical compounding might need different notions of “clean”. Clifford can say that the table is not clean enough for a chemical experiment while Cardinal Newman can claim that the table is clean enough to eat off of. It isn’t that the table is volitionally dirty for Clifford and clean for Newman, but rather given the situations - including their respective webs of beliefs as they are - the proper beliefs change: beliefs depend on purposes.

The result is that James says “Pascal’s argument… seems to be a regular clincher” is another example of his balanced style that I brought up in the introduction. It may seem to be a bit odd: if volition has so little to do with belief that even the great rationalists & agnostics are just navigating their web of belief then what does an argument that appeals to volition have to do with anything? Well, remember the criticism that James made in particular: the argument’s insufficiency in the light of symmetry. Pascal only found the argument convincing because he was 99% a believer already, this merely completed an in place process. At the time, this seemed like a critique but now it feels like a necessary part of any believing as such. The phrase “seems to be” is doing real work in this sentence. Seems to who? To Pascal, of course.

And yet this section is not a rehabilitation of Pascal’s wager. James is showing how the issue of belief formation leads a naive approach to difficulties. Belief is a very fraught topic, that’s the concluding sentence of this section. James’ real point is that the understanding - “healthy” as he puts it - of proper belief formation is going to be work.

Section IV

In the previous two sections, we began with the volitional seeming to have little place and ended with it seeming the volitional should have a central place. Now it is time in this section to transition from criticism to positive theory - where does James think is the right place? James puts his theory core thesis as follows:

Our passional nature must, and lawfully may, decide an option between propositions, whenever it is a genuine option that cannot by its nature be decided on intellectual grounds; for to say, under such circumstances, “Do not decide but leave the question open,” is itself a passional decision, just like deciding “yes” or “no,” and is attended with the same risk of losing the truth.

The right place for volitional belief formation is the genuine options - those belief options which are live, forced and momentous.

Having quoted fully half of this section, I will use this time to discuss two related theories: a precursor from Plato and downstream theory from Neyman & Pearson.

Consider Socrates’ speech on psychology in Phaedrus (and related speeches). Like James, Plato assigns the will a small but sneakily vital role. The metaphor Socrates uses for Phaedrus is that of a stout chariot with two winged horses. The rider of the chariot represents reason or the will. One horse is “guided by word and admonition only” but the other is so stubborn that it is “hardly yielding to whip and spur”. Thus the rider only somewhat controls the horses and chariot, resulting in a jagged and stressful path. Every element of the ride is necessary. If the horses were in agreement, the rider wouldn’t have the strength to control the path when they disagree. If the chariot were not strong enough to hold disagreeing horses, then the rider would have no control. Only by means of tension and balance can something as ephemeral as a thought control brute matter. Only by placing the rider (the will) in a chariot (the body) pulled in diverse directions by animal spirits (desires) can the rider have any control. Only that loose control can end up uniting the lovers in the beautiful city.

James, like many of the other agnostics of his generation, is trying to find a way to get the truth of Plato’s vision - the importance of the divided and tensioned nature of man for the efficacy of the will despite the subjective feeling that the tension is resisting the will - in a post Darwin world.

So moving on to Neyman & Pearson. A little history first. In the development of scientific statistics from Pascal to Karl Pearson the emphasis was on the emergence of patterns after many trials. The law of large numbers dominated early statistics. The basic idea was to throw away particular information about members of a sample to get the essentials of a mass of samples.

Things changed with Student (Bill Gosset) and Ronald Fisher. Their idea was to get the maximum amount of information out of a relatively small sample of a given level of reliability. Jerzy Neyman and Egon Pearson took the limited sample approach in a new direction. One of their contributions is the idea of “Type I and Type II Errors”. A maximally powerful statistical test is one that misses as rarely as possible for a given rate of false alarms. A false alarm is a type I error and a miss is a type II error.

James was not a statistician, but he anticipated the Neyman–Pearson insight that different kinds of error must be traded off. He recognized that genuine decisions - the ones covered by his axioms - must be made by powerful methods, and that powerful methods mean stricter tradeoffs rather than looser.

Section V

In this section, James comes to the question “Where is the truth in all this? Isn’t rigorous belief formation about finding the truth?”. He examines these questions by looking at two ways of considering truth, the empiricist (what we would call pragmatist) and the dogmatic.

First, look at the dogmatic. Think back to what James rejected in the method of Hyperbolic Doubt. James rejects that method because of its consequences. If one finds the indubitable belief, then one is done forever: “A system, to be a system at all, must come as a closed system, reversible in this or that detail, perchance, but in its essential features never!”.

This dogmatism is contrasted with the progressive pragmatism (what he calls “empiricism”) James abducts from scientific practice. James’ emphasis on scientific progress prefigures fallibilist philosophers of science such as Karl Popper and Imre Lakatos.

So what is truth without dogmatic standing grounds? For the James-Dewey-Schiller pragmatist, truth is correspondence in relevant aspects. Not an absolute correspondence that works for all people in all situations. The example James gives in Pragmatism is of the time-keeping-ness of a clock. The naive belief is that the clock is simply isomorphic to time as such. But then what is time as such. James argues the clock is isomorphic to (in the first place) our sense of greater and lesser quantities of time passing and (once the process of inquiry has begun) to the web of clocks real and hypothetical, with clocks being regarded as more and less accurate according to their agreements.

Coming back to Peirce, he would add that clocks must become increasingly isomorphic to the ideal possible clock which each actual clock approximates. Only from there do we get the static nature of truth. James never fully replied in print to this, expressing in his letters skepticism about the alleged infinite process and ideal possible clocks. But now we need to return from the truth to belief.

This section ends on a sobering note about belief formation and dogma. It’s all well and good to affirm pragmatism, but the blocking of Hyperbolic Doubt delimits the quantity of belief we can doubt. In fact, for all of pragmatism’s constant experimentation, the great mass of our beliefs will never be subjected to doubt.

Further, even the most demanding critics of belief, Bill Clifford for instance, must lapse into certainty. The point of doubt is belief formation, not preserving uncertainty. Go back and re-read Clifford’s essay, is this the work of a man wracked with doubts? No, it is firm and confident - in a word, dogmatic. This is not accidental, but psychologically necessary - “healthy” as James put it.

To sum up: our arbitrary psychological nature influences our decisions on all genuine options and dogmatism emerges unless an option is genuine. In essence, that consciousness of arbitrariness of belief is an ephemeral shade compared to the calcified belief result of the somewhat arbitrary decision. How do we cross this impasse?

Section VI

Our most important beliefs - the outcomes of our genuine choices - have an element of arbitrariness and yet this arbitrariness leaves no psychological trace but rather the opposite. Once formed, our beliefs lose the feeling of doubt and irony and become calcified: the half conscious and unreflective basis for future decisions.

Unreflective belief is the natural philosophy of man, a gadfly like Socrates is exceptional. Thus Dr James proposes a new role for evidence, quite distinct from the role espoused by the man James calls the “delicious Clifford”. Evidence is not just for doubt extinction, not mainly for ending the suspension of disbelief. Rather, evidence is a powerful tool for doubt creation. Clifford’s ship owner should not just have suspended belief by lack of evidence, he should have gathered evidence to realize he needed to suspend his belief. With evidence, the shipbuilder’s options would become live and the process of rigorous belief formation would start.

Man left to his own devices will tend towards a calcification. Whether from the laboratory to the historical-critical method, evidence and practice is the CLR that removes the calcium. Again, James here prefigures future fallibilist philosophers of science deeply.

James ends this section by rejecting ‘objective certitude’ while explicitly reaffirming what he calls ‘truth itself’. Objective certitude would be truth unconditioned by interpretive act. If it exists, then objective certitude is pure but weakly attached to ordinary reality. How an objective certitude ever got into a mind is a real mystery. Truth Itself is the truth in the context of interpretive action. Truth itself is a strong valuable metal due to its alloys with volitional belief creation and use-value. Think back to W. Edwards Demming’s analysis of the proposition “The table is clean.”. Do you want truth unconditioned by interpretive act or do you want a place to work/eat? Do you want objective certitude or the truth itself?

Section VII

“‘Believe truth!’ ‘Shun error!’—these, we see, are two materially different laws; and by choosing between them we may color differently our whole intellectual life.”

This is how James motivates his innovative idea that it is our volitional attitude toward risk which is decisive when faced with genuine options. It’s difficult to see James’ analysis when faced with purely verbal examples, but fortunately a simple numerical example helps significantly.

In this example, the belief under consideration is whether interest rates will rise, stay the same or fall. This is actually not as different from Clifford’s example of the ship owner as it may appear - the ship owner had a choice between using his capital to launch the ship or do something else. Clifford correctly notes he should have taken into account evidence. Even if by chance everything worked out right, the ship owner was taking unnecessary risks with human lives.

Coming back to the numerical example, the use-value of beliefs about the interest rate comes from the ways they will affect investment decisions. We will assume this belief is live, forced and momentous for the investor who either holds cash or invests in this situation as well.

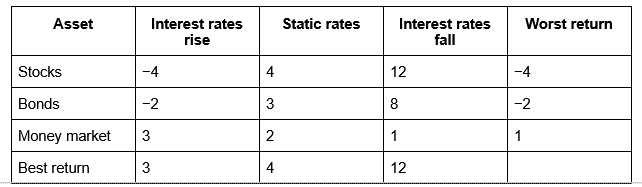

The table of returns are below. The table is an illustrative table from Wikipedia, not actual returns. Put in words, in this table stocks strongly anticorrelate with interest rates, bonds weakly anticorrelate with interest rates and money markets weakly correlate with interest rates. Further, the level of fluctuation depends on the asset: stocks have large fluctuations, bonds medium and money market small. How do James and Clifford help us understand this situation?

Clifford is writing directly about our attitude towards evidence, but James interprets his maxim as an attitude toward risk: “he who says, “Better go without belief forever than believe a lie!” merely shows his own preponderant private horror of becoming a dupe.”. One can see that James sees Clifford in the light of “maximin” decision making. Maxmin is a rule for making choices: make the choice which makes the best of the worst outcomes. Of course, this is interpretive on James’ part, not literally in Clifford’s essay. But under James’ interpretation, Clifford is strongly recommending the safe but dull money market.

Applying James analysis, we see the maxmin returns rule is not a necessity. The decision rule is a particular attitude toward risk. “I myself find it impossible to go with Clifford.”, he reports. I understand James’ temperament as aligning better with a minmax “regret” approach. The regret of a choice in a situation is the difference between the payoff of that choice and the best choice in that situation. Numerically, stocks have a max regret of 7 (if interest rates rise), bonds have a maximum regret of 5 (if interest rates rise) and money markets have a maximum regret of 11 (if interest rates fall). Thus I see James as preferring Bonds to Money Markets in this artificial situation.

In choosing a different rule, James does not mean to replace Clifford. He is simply reporting his own psychological attitude towards risk: “For my own part, I have also a horror of being duped. But I can believe that worse things than being duped may happen to a man in this world, so Clifford’s exhortation has to my ears a thoroughly fantastic sound.”. But that fantastic sound had a benefit: Clifford’s tune was very definitely in pitch. How does James’ psychologism avoid thorough formlessness? That we shall see in the next section.

Section VIII

James closed the last section by saying that certain attitudes towards risk are “like a general informing his soldiers that it is better to keep out of battle forever than to risk a single wound. Not so are victories either over enemies or over nature gained.”. Let’s look at an example from the statistics of warfare due to Egon Pearson:

“Two types of heavy armour-piercing naval shell of the same calibre are under consideration; they may be of different design or made by different firms. Since the cost of producing and testing a single round of this kind runs into many hundreds of pounds, the investigation is a costly one, yet the issues involved are far reaching. Twelve shells of one kind and eight of the other have been fired; two of the former and five of the latter failed to perforate the plate. In what way can a statistical test contribute to the decision which must be taken on further action?”

The hypothesis to test is “Is the proportion of functioning shells made by company X greater than that of those of company Y?”. The evidence is company X’s shells worked 10 out of 12 times (pi_x=5/6) and company Y’s shells worked 3 out of 8 times (pi_y=3/8). This is practically right on the boundary for statistical testing - it is hard to tell from this evidence whether the null hypothesis (pi_x = pi_y) or the alternative hypothesis (pi_x > pi_y) better fits the data.

Let’s dig deeper into this example. Tests of close sizes give different answers to the hypothesis test. In the Neyman-Pearson way of thinking, the size of the test determines a likelihood ratio threshold for the rejection of a null hypothesis. Cosma Shalizi has shown that the likelihood ratio threshold can be interpreted as the shadow price of the power of the test. Now, to connect this up with James we must remember the nature of a shadow price: shadow price is a marginal concept. The cost of forming a definite belief is the opportunity cost - the possible beliefs one gives up. At what cost a null hypothesis? Similarly, in James, rigorous belief formation is exactly belief formation at the margin: “The most useful investigator, because the most sensitive observer, is always he whose eager interest in one side of the question is balanced by an equally keen nervousness lest he become deceived.”.

Perhaps it should be noted that it is here, at the root insight, James finally cites William Ware. Whatever the source, James has at this point set up all the wires, we are now ready to close the final switch and complete the circuit. James has finally cashed in the promissory note that this is an ordinary part of scientific reasoning, with the example of Röntgen (or X rays) in medicine. Such practices were still novel in 1896. Though not statistical, the linked paper shows exactly the kind of delicate trade off James has discovered: “I have been much impressed by the practical importance of the Rontgen ray process in surgery, but in no instance more than in this, where, in a case in which every hour had become valuable and every effort at exploration dangerous, it substituted accuracy and promptness for otherwise unavoidable uncertainty and delay.”.

Section IX

Before moving into this section proper, let’s look closer at the above surgical case study. Dr J. William White had to form beliefs about a jack stuck in a small child’s throat in order to save the little girl’s life. For the emergency room surgeon, the decision whether or not to knife open a two year old girl’s throat or to try and pry out the jack with forceps is live, forced and momentous - a genuine choice. James has shown that the surgeon is thinking rigorously exactly when he is at the locus where there is a tradeoff between different types of error.

James does not see this as an isolated incident. James argues that what he calls “moral questions” are always what he calls “genuine options”: live, forced and momentous. Thus James finally is able to give a reply to Clifford as a moralist of belief formation, not just as an analyst of such. It may be helpful to paraphrase James’ analysis in a simple maxim. To paraphrase boldly in bloodless modern language, “Thou shalt hold to such belief formation processes as to be sure your beliefs are at the margin of the tradeoff between the two types of error.”.

James’ analysis, even in the maxim paraphrase above, has many advantages. The maxim brings in evidence in the right ways: doubt creating and resolving, as informing but not decisive, etc.. It works with self-fulfilling and self-negating prophecy in the right way: “Where faith in a fact, based on need of the fact, can create the fact, that would be an insane logic which should say that faith based on inner need, and running ahead of scientific evidence, is the ‘lowest kind of immorality’ into which a thinking being can fall.”.

We finally see how James’ approach accommodates without coddling those who cry “Peace!” when there is no peace. James opened the door to a coherent understanding of “Optimism of the will, Pessimism of the intellect.”.

Section X

Wasn’t this talk going to be about the philosophy of faith at some point? James, having his analysis of rigorous belief formation and its connection to moral questions at hand, is now able to loop back to the question of religious belief.

What is, in terms of belief, a religion? James gives two basic poles that define religious belief: “First, she [religion] says that the best things are the more eternal things, … And the second affirmation of religion is that we are better off even now if we believe that first religious truth.”.

In making this definition of religion in terms of belief, James has chosen a perspective. As T S Eliot puts it in his introduction to Pascal’s Pensées:

“The Christian thinker … proceeds by rejection and elimination. He finds the world to be so and so; he finds its character inexplicable by any non-religious theory … [his religion] account[s] most satisfactorily for the world and especially for the moral world within; and thus, by what Newman calls “powerful and concurrent” reasons, he finds himself inexorably committed to the dogma of the Incarnation. To the unbeliever, this method seems disingenuous and perverse; … he would, so to speak, trim his values according to his cloth, …The unbeliever starts from the other end …: Is a case of human parthenogenesis credible? and this he would call going straight to the heart of the matter.”

James would certainly not treat claims like human parthenogenesis as candidates for a genuine tradeoff between types of error. Such claims simply do not arise as live options for anyone. It is on the basis of such issues that, ten years before this lecture, Nietzsche would encapsulate the troubles with belief leaning agnosticism with a pithy maxim: “Aber eine Neugierde meiner Art bleibt nun einmal das angenehmste aller Laster, - Verzeihung! ich wollte sagen: die Liebe zur Wahrheit hat ihren Lohn im Himmel und schon auf Erden.”.

For James, the interesting question of religious belief is never the ontological question of the mechanics of a virgin birth. The religious question is, for James, a moral quandary - and thus, ipso facto, a genuine option. James then checks each of his three axioms to be sure. He finds in accordance with his earlier analysis, that belief and disbelief then are influenced decisively by our attitudes towards risk.

James, of course, did have ontological opinions. In this section, he has early defenses of his later principles of “piecemeal supernaturalism” and the “pluralistic universe”. But this section of James looks forward to his future work. In Varieties Of Religious Experience, James continues to bracket away the question of existence of eternal things and investigate religious questions as they are on earth.

And so, James ends his sermon with a defense of tolerant agnosticisms as a spectrum of religious hypotheses. Like Popper would later, James also sees a connection between fallibilism and tolerance. Whatever way one’s ontological beliefs lean, the Jamesian tolerant agnosticisms give the parishioner a noble investigative task, and James would continue to be one of its great investigators.

Conclusions

The reception to “The Will To Believe” was enthusiastic and yet it’s difficult to summarize what exactly the reception was. Both Ralph Barton Perry and Jacques Barzun in their books on William James remark how little intelligent commentary for such a popular lecture. The essays anti-Cartesianism, the phenomenological discovery of the structure of belief formation and the extremely important idea of rigor entailing an accuracy/precision trade off were nowhere to be found in the commentary literature.

Part of this reason is historical. After James, the dominant movement in English-language philosophy was so-called “analytic philosophy”, especially its “ordinary-language” strand. G E Moore can be taken as a representative member of the tribe. Moore’s “Defense Of Common Sense” demonstrates his highly original method. Instead of Descartes’ cogito argument of man as a thinking thing, Moore argues that the foundational knowledge is “There exists at present a living human body, which is my body.”. This is not the original part. According to Brian Magee, this insight is also to be found in Schopenhauer. But what was original in Moore is not this foundational sentence, but how he defuses the possibility of a hyperbolic doubt in this case. In essence, Moore argues that we clearly do know this sentence is true and that any definition of “knowledge” which failed to reflect this is a poor definition of knowledge.

In this manner, ordinary language philosophy (at least in its early Moorean form) rejected Cartesian doubt. And yet from what I have seen, Moore remained committed to an ideal of philosophical clarity. It seems to be assumed increasing precision would generally aid accuracy, rather than involve essential trade-offs between precision and accuracy of the sort James emphasizes. I have never seen anything in Moore or Bertrand Russell about such trade-offs. Modern analytic philosophers like Lara Buchak considered this trade off more carefully.

Still, core to the approach of Moore and Russell specifically was the concept of “philosophical problems”, places where language led the user astray. The ordinary language philosopher could then lead the language user back to the truth with the tool of linguistic analysis. There is thus no need for the trade offs of belief formation under uncertainty, as the language user is assumed to be “confused” rather than, say, facing a genuine decision under uncertainty. Wittgenstein ended his Tractatus by noting that the “confusion” concept implied that philosophical problems, so conceived, are not real problems at all.

The above paragraphs admittedly paint Moore and Russell’s position with a broad brush. To put a fine point on it I will post Bertrand Russell’s commentary on the will to believe (from History Of Western Philosophy) in its entirety so that you can see how distant this school of thought was from James.

“The Will to Believe argues that we are often compelled, in practice, to take decisions where no adequate theoretical grounds for a decision exist, for even to do nothing is still a decision. Religious matters, James says, come under this head; we have, he maintains, a right to adopt a believing attitude although “our merely logical intellect may not have been coerced.” This is essentially the attitude of Rousseau’s Savoyard vicar, but James’s development is novel.

The moral duty of veracity, we are told, consists of two coequal precepts: “believe truth,” and “shun error.” The sceptic wrongly attends only to the second, and thus fails to believe various truths which a less cautious man will believe. If believing truth and avoiding error are of equal importance, I may do well, when presented with an alternative, to believe one of the possibilities at will, for then I have an even chance of believing truth, whereas I have none if I suspend judgement.

The ethic that would result if this doctrine were taken seriously is a very odd one. Suppose I meet a stranger on the train, and I ask myself: ‘Is his name Ebenezer Wilkes Smith?’. If I admit I do not know I am certainly not believing truly about his name; whereas, if I decide to believe that that is his name, there is a chance that I may be believing truly. The sceptic, says James, is afraid of being duped, and through his fear may lose important truth; ‘what proof is there,’ he adds, ‘that dupery through hope is so much worse than dupery through fear?’ It would seem to follow that, if I have been hoping for years to meet a man called Ebenezer Wilkes Smith, positive as opposed to negative veracity should prompt me to believe that this is the name of every stranger I meet, until I acquire conclusive evidence to the contrary.”

This certainly illustrates Barzun’s frustrations with finding engaging commentary on “The Will To Believe”. Russell’s example meets absolutely none of James’ axioms:

The belief is not live. James explicitly defines “liveness” as a relation between a hypothesis and a believer. Russell states that he thinks there is little possibility this person is named Ebenezer Wilkes Smith. A belief Russell already treats as implausible is dead on arrival.

The belief is not forced. Russell’s example allows suspension of judgment, many alternative names and no practical necessity to decide. James’s point is precisely that suspension is sometimes not an option, rather than suspension never being an option.

The decision is not momentous. Nothing of value turns on the belief that the man is named Ebenezer Wilkes Smith, no opportunity is lost by waiting and no irreversible consequence follows. James’ whole approach is about balancing the opportunity costs of different beliefs.

Thus Russell, having expounded an example carefully constructed to not exemplify James’s axiomata, notes that James’ constructions do not go through. Remember, James’ analysis is about why organisms faced with genuine options spend the energy to make difficult decisions informed by their attitude toward risk. Not that the types of risk have a trade off generically, but they have a trade off at the margin. Russell’s argument not only does not contradict James’ “The Will To Believe”; Russell’s conclusion is implied by James’ approach!

What this shows is that James is not merely a historical precursor, something that has been tried and discarded. We can recognize his ideas in modern methods like Neyman-Pearson because his thought is still lively and powerful. William James’ ethic of belief is beautiful: structured and yet pluralistic. I will go through some of the schools of ethical thought and what I believe James has affinities with and stands opposed to in each case:

Virtue ethics

Accepts: the centrality of practical wisdom (φρόνησις) and healthy-mindedness (similar to εὐδαιμονία); that the good consists of cultivating virtues such as tolerance (ἐπιείκεια) and courage (ἀνδρεία)

Rejects: the detachment of virtues from consequences

Deontology

Accepts: the fundamental importance of deep structure (i.e. presenting genuine options) in moral decisions

Rejects: the decisiveness of said deep structure

Utilitarianism

Accepts: the evaluation of moral acts in terms of consequences

Rejects: the disjunction between means and ends, the emphasis on individual acts instead of habits (virtues)

With all this, we can at last see that William James was not just a great psychologist and philosopher, he was a brilliant moralist of belief.