Review Of Hyman Minsky's "John Maynard Keynes"

What Does Minsky Mean Now That The 2010s Are Over

“As [the imagination’s] ideas move more rapidly than external objects, it is continually running before them, and therefore anticipates, before it happens, every event which falls out according to this ordinary course of things. … But if this customary connection be interrupted, if one or more objects appear in an order quite different from that to which the imagination has been accustomed, and for which it is prepared, the contrary of all this happens.”

Adam Smith, “The Principles Which Lead And Direct Philosophical Enquiry, As Illustrated By The History Of Philosophy”, Section 2: Of Wonder, or of the Effects of Novelty

A Table of Contents for a Long Post

What Do We Read Minsky For and What Should We Read Minsky For?

Minsky and Capital Theory in the Designer Economy

Reading Minsky Properly

Minsky’s Intellectual Environment

Part 1: The Paradoxes Of Rationality

What Exactly Do We Mean By Rationality

Paradoxes of Rationality in the Work of Minsky’s Contemporaries

Part 2: The Contradictions Of Growth

Quantitative Models of the Qualitative Transitions of Growth

Growth, Demand, Inventory and the Revaluation Impulse

Minsky’s Economics

Part 1: Demand Rules Employment

Neoclassical Growth and the Fifth Channel From Demand to Employment

Part 2: Investment Rules Demand

Interlude: The Pure Theory Of Strategy

It’s Time For Some Game Theory

Part 3: Liquidity Opens Strategy

Liquidity Opens Strategy; Unknowledge Closes It

Conclusions

What Do We Read Minsky For and What Should We Read Minsky For?

“… Keynes put forth an investment theory of fluctuations in real demand and a financial theory of fluctuations in real investment.”

Hyman Minsky, John Maynard Keynes, Chapter 3: Fundamental Perspectives

Maybe you remember 2006 well. A young fresh face named T-Pain topped the music charts, film bro classic In Bruges dominated theaters and the international banking system violently collapsed causing an international financial crisis which would dominate global politics for the next ten years.

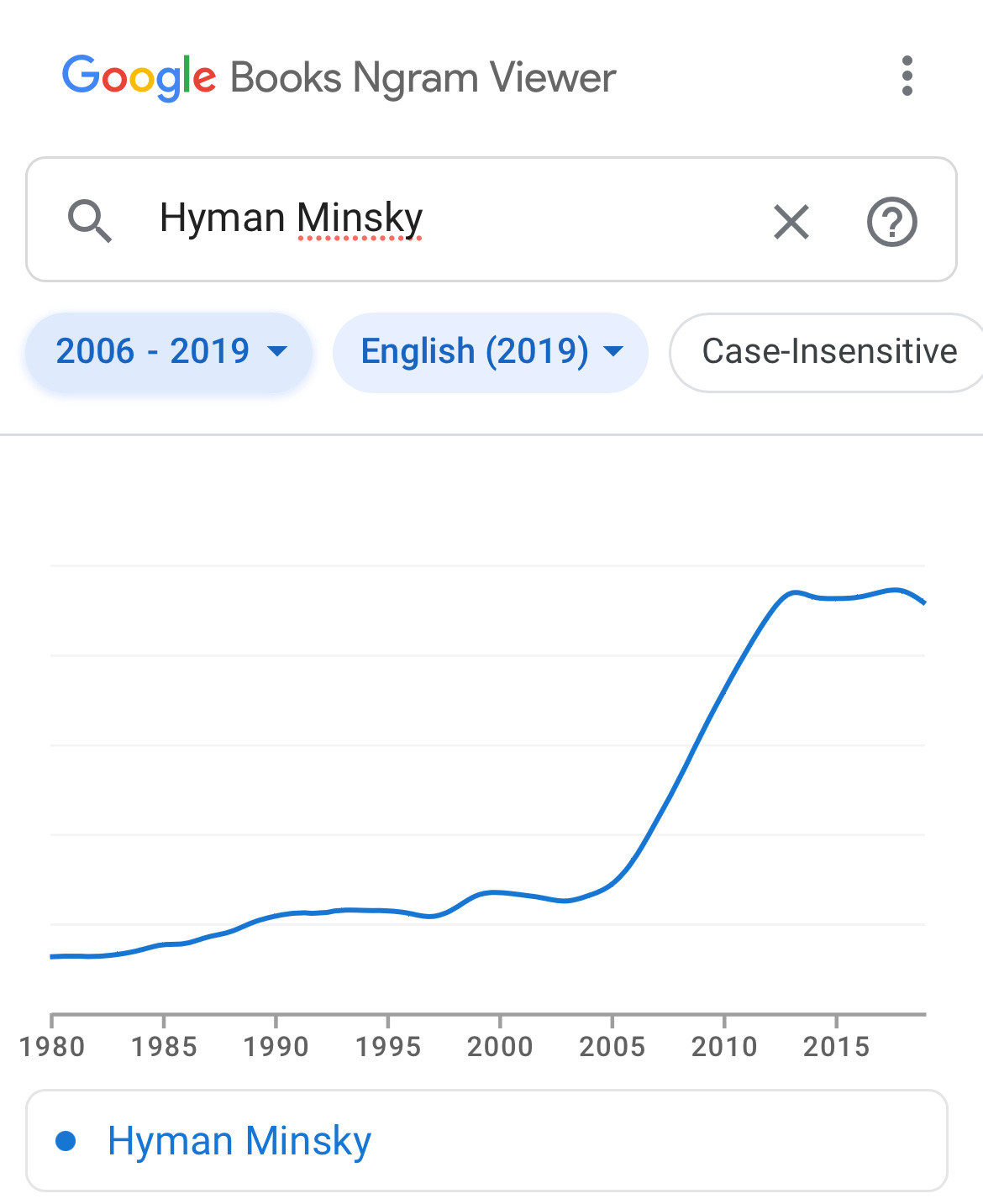

In the wake of the rapidly developing global financial crisis, many people turned to the economic sage Hyman Minsky for guidance. In some sense, this literature was a boon. After all, Hyman Minsky was a great economist, and it’s always good when they see a comeback. But in another, more accurate sense, this pretense was bad, and the literature it brought about confused and reduced Minsky’s economics to such a degree that they could easily fit in a few lines of newsprint.

First of all, the phase change in Minsky citations seems to have been triggered by the Lehman Brothers collapse. While this collapse was certainly important, one hardly needs a sage to analyze it. Equally annoyingly, in the trendiness of collapse finance, Minsky was absorbed as a bit player in the then-current acronym debates - MMT, QE, TARP, etc.. But most importantly, the reputation of Minsky as a business cycle doomsayer has severely reduced the audience of his theories, and broadly reduced the comprehension of his non-audience.

This started long before 2006. See, for example, Paul Samuelson’s ‘A Personal View on Crises and Economic Cycles’ (paper 497 in volume 7 of his collected papers). Samuelson is certainly justified in asking if the world needs yet another voice constantly shouting “A qualitative credit crisis is in the intermediate-term cards. Wolf! Wolf!”. Is Minsky’s role merely to assign a determinate name and career to the fact of that voice?

Assuredly not: Minsky’s work is even more relevant now than it was in the months and years following the financial crisis. The way the COVID19 Mother Of All Demand Shocks has revealed that, for example, our JIT production infrastructure was more fragile than anticipated, is far more Minskyian than the collapse of Lehman Brothers was.

Minsky and Capital Theory in the Designer Economy

So how does Minsky help us solve this problem? Asking companies to go back to 1950s production methodologies is not a plan. Creating the conditions for the production base to gravitate to more stable methods requires an understanding of inventory as a part of the portfolio of a company. Revolutionary, evolutionary or even liberal: you still have to do capital theory.

Taking a Keynesian approach to capital theory means identifying what kind of part inventory is in the portfolio of a company: it is an illiquid one. Holding goods means being unable to hedge the risks involved in not-holding cash. Because of this fact, a capitalist economy is structurally stuck with a deep paranoia. The ‘fear of goods’ is built into the heart of the manufacturing processes because inventories, as a kind, intrinsically move slower than merely financial processes. Inventories are also creatures of time and timing: of changing demands, changing capacities, and of the need to put them somewhere for the duration of their time as inventories.

This is at the heart of the “financial theory of investment” which powers Minsky’s model. The case I wish to make in this review is that rather than the mere stormcrow he is often made out to be, Minsky was instead a prophet of the designer economy.

At the most general level a Designer Economy is an economy which aims to equilibrate through the creation of possibilities rather than by the elimination of possibilities. Our solution to the oft-justified paranoia of the capitalist is not to play into it and allow him to bunker down, but instead to help him develop habits that allow him to open up: a kind of administrative therapy. As Spinoza put it:

PROPOSITIO LXXIII : Homo qui ratione ducitur magis in civitate ubi ex communi decreto vivit quam in solitudine ubi sibi soli obtemperat, liber est.

Spinoza, Ethica, Pars quarta: ‘De servitute humana seu de affectuum viribus’

The ideas Minsky developed will be even more important to the success of a Designer Economy than they were to explaining the global financial crisis.

Reading Minsky Properly

But one truth must be admitted. Minsky is even harder to read now than he was at the turn of the century. The writings themselves are difficult, but in 2008, the world’s problems were financial, Minsky’s home turf. A financial collapse fed forward into an investment desert which fed forward into a decade-long demand shortfall. Contrariwise, in 2023, our problems are pandemics, wars and climate change which Minsky’s writings are not directly about. Despite this, the deductive chain that links his premises to the topics that make his work vitally important to today’s economic issues is strong but long.

Why then has Minsky’s Ngram risen? I fear that discussions of Minsky often turn into

a list of reasons to read/not to read Minsky that make it clear the list’s author has not read him

inscrutable insider baseball,

Political/Philosophical/Personal jeremiads,

jargon unintelligible to anyone who would need to hear a discussion,

or, worst of all, high quality economic analysis that tells truths many don’t want to hear.

Like Chedorlaomer, I wish to destroy four of these five cities. I will start Minsky’s case by reading him into the intellectual environment he thrived in, which will give us the right choice of tools to understand him. Once we understand the broad sweep of his intellectual environment, we can plow through the land Minsky covers. That is to say, the Finance -> Investment -> Demand -> Output channel mentioned above. I find it easiest to go backwards:

Demand -> Output

Investment -> Demand

Finance -> Investment

After this groundwork is laid, we can close out with a few finer points.

As a result of this approach, some of the most important and well known of Minsky’s theses won’t be mentioned at all and others will be restated in my own peculiar argot. This therefore is more a prolegomenon than a review. My only hope for the resulting review is that you are able to read Minsky with fresh eyes.

Minsky’s Intellectual Environment

Part 1: The Paradoxes Of Rationality

Minsky’s theory may seem strange. Who asked for a financial theory of recessions? Do we think sophisticated investors structure portfolios that crash? What arrogance to think sophisticated investors with decades of experience just work their minds toward their own doom, but mere academics can do better.

Some have even asserted Minsky violates some “assumption of rational behavior”. There is an analogy in this accusation to the economics of machinery, as highlighted by one of Minsky’s closest friends. Naively, one might believe that the introduction of a more efficient machine must be non-decreasing in output, since society can always choose to simply not adopt a technique that reduces output (and to the extent it cannot, that is a problem of monopoly rather than machinery). This misses that the effect of a labor saving invention can be to raise rents and thereby reduce production in the long run. In a mythical Ireland where the nobility eats cake and the peasants potatoes, improving wheat land means the nobility has less need to suffer the existence of the peasantry.

Samuelson above and Kindleberger elsewhere see these intuitive mistakes as examples of the infamous ‘mathiness’ of current economic theory - one can often get away with an unsupported assertion by dropping a technical sounding buzzword.

The buzzword is “Pareto optimality” for machinery and “rationality” for finance. If you are versed in the jargon, you might notice these two buzzwords - when used properly - denote the same closely analyzed concept. But finding the buzzworder’s mistake is only half the battle. Actually developing a theory that replaces buzzwords with good sense is the other.

What Exactly Do We Mean By Rationality

Let’s focus on rationality. Rationality is a grand subject: rationality per se has been a goal and object of investigation ever since The Enlightenment. We shall soon see that Minsky's analysis of rationality in particular highlights what is often called a “paradox of rationality”. A paradox of rationality is a particular case of the famous “fallacy of composition”: the rationality of each member of a group doesn’t entail group rationality. These are well known enough that I can name three examples off the the top of my head:

The Paradox Of Thrift, in which a group of rational savers cause a reduction in total saving,

Tendency of the profit rate to fall, in which a group of rational capitalists invest until their original investments can’t be validated, and

Minsky’s Example: a group of investors who invest in the status quo destabilize the status quo. (See, for instance, a crowded trade)

Partly under the influence of Keynes and partly because of the game theory revolution, economists and philosophers became interested in a particular paradox coming from the organic nature of judgment and action just as Minsky was maturing as an economist. The basic economic paradox is simple: a person who may judge rationally often must act “irrationally”.

An extreme example can be given, if I am allowed some license. In 1945, the Japanese high command was aware that it had lost the war. They planned to draw out the conflict while offering conditional surrenders in order to go to the negotiating table in a strong position. The Japanese high command posited that they were willing to see the home islands flattened in order to avoid seeing the home islands flattened. This posit became a pose which did not work. The Japanese high command eventually went to the negotiation table with an unconditional surrender.

Paradoxes of Rationality in the Work of Minsky’s Contemporaries

We can see how broad this fascination with paradoxes of rationality became by looking at three contemporaries of Minsky, at least one of which was influenced by the example of the Japanese high command. Those three are Thomas Schelling, Robert K Merton and David K Lewis.

Thomas Schelling is well known for fascination with paradoxes of rationality, which he sees as a distinction between micromotives & macrobehavior (i.e. the fallacy of composition). But Schelling didn’t start off as a strategy theorist, but as a Keynesian economist. Indeed, Schelling first got interested in paradoxes of rationality by the famous “paradox of costs” in Keynesian economics!

That Schelling moved from economics strictly speaking to general strategy theory shows that economics was not the only field discovering paradoxes of rationality. Around the same time, Robert K Merton was writing influentially on self-fulfilling/negating prophecies. Like the economists Minsky and Schelling, Merton was fascinated by how actors in a capitalist economy deal with the unyielding uncertainty of life. The center of his theories was on the unending tension between imitation and adaptation. He created a model in which an actor within an organization imitates his “role model” until they predict that imitation will not fulfill their desires. In that case, they attempt to adapt and the organization then must adapt to this adaptation. We see then that there is a fundamental paradox of rationality. In this almost cybernetic vision, a self-defeating organization is much like a self-defeating prophecy, snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

Speaking of almost cybernetic visions, we come to the last of our trio: David K Lewis. Lewis was a so-called analytic philosopher in a tradition anchored by his mentor Quine. This variety of philosophy emphasized mere logical analysis, but made up for this by vaunting classical first order to almost religious levels. This technique oriented philosophy unsurprisingly reached a polish and sheen rarely seen in any academic discipline. Lewis showed that a group of rational organisms could use arbitrary symbols to coordinate non-arbitrarily. If each organism acts according to a rule “if I see signal s, then I do action a.”, then in a very real sense signal s ‘means’ “We are in situation n, which makes a the best course of action.”. This is an example of a paradox of rationality in reverse: rules which are arational to the individual beget group rationality. There is actually a quite direct contact between Lewis’s conventional signaling analysis and uncertainty, as a more general statement of rules of behavior is more like “If the signal is s with probability p, s’ with p’, s’’ with p’’, etc, then I do action a with probability q, a’ with q’, a’’ with q’’, etc.”.

This has started to take us away from our goal, and besides the point has been established. In the introduction, we noted that it’s not difficult to see rational irrationality as a property seen in economic failures. We have now gone over briefly how the rationality which structures the micromotives of agents do not necessarily strongly constrain the macrobehavior of society. It’s sheer mathiness to go from rational agent to rational system. What it now comes time to do is establish how this ‘paradoxes of rationality’ applies to economic growth.

Part 2: The Contradictions Of Growth

“...quis dicet, an sequens experimentum non discessurum sit nonnihil a lege omnium praecedentium? ob ipsas rerum mutabilitates. Novi morbi inundant subinde humanum genus, quodsi ergo de mortibus quotcunque experimenta feceris, non ideo naturae rerum limites posuisti, ut pro futuro variare non possit.”

Gottfried Leibniz, Leibnizens Mathematische Schriften, “Letter To Jacob Bernoulli December 3rd, 1703 ”

The concept of economic growth developed from the same enlightenment theorists that promoted the concept of rationality. In fact, the hard right wing of the enlightenment, such as Swift & de Maistre, claimed there was a paradox of rationality in Leibniz & Spinoza. They proposed that a group of rationalists would be unencumbered by social restraints and thus immediately overthrow all progress. This is A O Hirschman’s “Perversity” from Rhetoric Of Reaction.

A more interesting theory developed from the moderate right of the Enlightenment: Mandeville, Hume and Adam Smith. Growth is a paradox of rationality, but the paradox is that a group of rule-followers can form revolutionary theories. We might recall Adam Smith on the history of astronomy. Out of the sense of wonder, the ancient astronomers created a structural theory of the cosmos based on the four part classification of celestial objects into Sun, moon, planet and fixed stars. By a process much like a paradox of rationality, the dynamism of wonder was replaced with the husk of belief. Eudoxus was then, by Smith’s lights anyway, led by his unshakable belief in this system to overthrow it: making the theory geometrically precise required more spheres than the obvious classification makes it seem. “Work-to-Rule” strikes are an earthier variety of a similar process.

But this is to talk about growth in general, including qualitative improvement. Ever since Adam Smith, economists tend to think of economic growth strictly in terms of quantitative growth without qualitative change.

Quantitative Models of the Qualitative Transitions of Growth

Let’s be precise for a change, although it requires a detour from Minsky per se. Adam Smith defines growth as an increase in the intensive margin. Compare two identical pin factories vs one pin factory twice as large. The second one has more output per capita due to more division of labor.

The modern version of this quantitative growth theory is the theory of exogenous growth which started with Wicksell and was perfected by another one of Hyman Minsky’s close friends. I will go through a particularly comprehensible case because my goal is exposition not criticism. Besides, the right goal for exogenous growth theory is precision rather than strict accuracy or generality. As an approximation, assume all n+1 capital funds are rights to physical capital goods. Output per capita will be further assumed to be a fixed and well behaved function of all the capital funds in the economy in real value terms. This can be best comprehended in a couple equations:

where k_i is the value of capital good i, p_i is the unit price of capital good i, q_i is the quantity of capital good i, P is a price deflator, N is the quantity of labor in the economy, y is real output per capita, b is a factor of proportionality and a_i is the weight of good i. Dimensional considerations tell us that the a_i sum to 1. The power of the model comes from assumptions like assuming the weights constant (or similar assumptions for different functional forms). The additional term b is usually allowed to be a function of time, interpreted as “technical change”.

In 1956, Robert Solow used this simplified model to argue for the stylized fact that technical change contributed more to growth than capital deepening did. This was bound to be controversial, but strangely enough neither this result nor its negation became a part of economics. Rather the style of model became de rigeur for so-called mainstream economics. This mystifies everyone, including Solow.

This approach ignores, quite deliberately, crucial qualitative aspects of economic growth. Returning to Adam Smith, look at the example of technological change (his comment is deleted from Wealth Of Nations, but present in the Canan edition). Implementing Jethro Tull’s steam powered seed drill improves the intensive margin of the same labor hour on the same land producing the same wheat. But this causes a revaluation of all the hand powered seed mills. So we see that holding consumption goods - wheat - fairly constant so that y has a stable meaning, means that production processes are constantly changing. Then in order to compare outputs at different times, the k_i cannot be the market value of actual capital goods, as each capital good is constantly being revalued. Instead, it has to be some sort of index. This leads us into the muck of the ‘measurement of capital’. As Robert Solow put it:

“If you think of growth as an uninterrupted, smooth process, and if the economy is in some kind of a natural equilibrium all the time, then you can give a fairly complete analysis of that. But when a surprise happens, a shock of some kind, a war, maybe a big invention, any kind of a disturbance, then the existing real capital – machinery and buildings, computers, telephones, and all that – has to be revalued in smooth equilibrium conditions. This is what capital theory is about. You can talk in pretty precise terms about what the value of a capital good is. The reason why, when a disturbance occurs, you cannot do that any more, is because the value of the capital good depends on the present discounted value of its future earnings. The essence of the surprise is that you thought you knew what your earnings would be but it turns out that you don’t. And then the question is to understand in exact detail what happens then and how the economy does or does not get back to a different equilibrium state. You have to be able to get a grip on how capital goods are valued under such circumstances of real uncertainty, that is, uncertainty that cannot be described by probabilities. That’s very difficult. I have never had a very good idea. Nobody else has ever had one either. That’s a very important question, it’s not esoteric.”

Robert Solow in Karen Ilse Horn’s Roads to Wisdom, Conversations with Ten Nobel Laureates in Economics, emphasis mine

We will return to the time structure detailed by Solow later. For now, the main point is economic growth often comes not from the same goods just more, but rather, from different goods entirely. This results in two related paradoxes of growth: ‘creative destruction’ and ‘fear of goods’.

Growth, Demand, Inventory and the Revaluation Impulse

Because growth involves qualitative change, a firm cannot guarantee that there will be the same demand for their output after the change as before. Simply from an uncertainty management point of view, a firm is usually better off holding cash rather than a good of near equivalent value in this situation. As Shigeo Shingo said, inventory is evil. This is the ‘fear of goods’. This uncertainty can shadow you even if your wares are superior to the new substitute goods, which is the body of the process of ‘creative destruction’.

Having now hit two famous buzzwords, it will do to make sure we really have done the work and not just dropped them because it feels good. In Part 1 of this section, we re-aired some famous pitfalls in the application of rationality. Now we have claimed that economic growth intrinsically involves a paradox of rationality: firms, simply by trying to grow in value, subject themselves and each other to downward value revisions. To paraphrase Popper in the introduction of The Poverty Of Historicism, it is in qualitative technical change where we expect our predictions to be the least successful - if we can predict which capital goods would bring the highest return, then why haven’t we already bought them?

Paradoxical valuation is a very important question, it’s not esoteric. If you drive a barely functional $4,000 clunker to work every morning then you can lose food stamps and thereby lose your family’s access to a good dinner because of the lurching pricing dynamics of the used car market. Minsky’s economics tries to come to terms with an economy characterized by pervasive growth-driven valuational paradoxes of rationality by following the chain of causality from finance to output. As stated in the introduction, we will follow that chain backwards: Demand -> Output, Investment -> Demand and Finance -> Investment. Like Ancient Greek plays, we will break up the economics with a Satyr play: a brief interlude into the pure theory of strategy. The strategies created by such a paradox ridden valuation system are the stuff of Minsky’s economics itself.

Minsky’s Economics

Part 1: Demand Rules Employment

“… the physical conditions of supply in the capital-goods industries, the state of confidence concerning the prospective yield, the psychological attitude to liquidity and the quantity of money (preferably calculated in terms of wage-units) determine, between them, the rate of new investment.

… changes in the rate of consumption are, in general, in the same direction (though smaller in amount) as changes in the rate of income. The relation between the increment of consumption which has to accompany a given increment of saving is given by the marginal propensity to consume. The ratio … is given by the investment multiplier.

Finally, if we assume (as a first approximation) that the employment multiplier is equal to the investment multiplier, we can, by applying the multiplier to the increment (or decrement) in the rate of investment brought about by the factors first described, infer the increment of employment.

An increment (or decrement) of employment is liable, however, to raise (or lower) the schedule of liquidity-preference;…

Thus the position of equilibrium will be influenced by these repercussions; and there are other repercussions also.”

John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money, Chapter 18, ‘The General Theory of Employment Restated’

The above is more or less Keynes’ model which he developed within his background logic in the first four books of The General Theory (GT). Feedforward from dynamics in financial portfolios consisting of physical and financial capital is stabilized, with lots of leakage, by feedback from dynamics of employment vs liquidity preference.

Right now, we will concentrate on the connection of demand to employment. Classical theory allowed for four sources of unemployment: friction, leisure preference, productivity in wage-good industries and price of wage goods. This creates a specific dynamic: “That which we call dearness is the only remedy of dearness: dearness causes plenty.” - this is how Bagehot summarizes what he believed valuable in the Physiocrats. Say’s law was “There is no real[, i.e. long lasting,] dearness but that which arises from the cost of production.” (David Ricardo, On The Principles Of Political Economy And Taxation, Chapter 20: Value and Riches, their Distinctive properties). This is the reverse of Keynes’s position: rather than demand pulling resources into employment, the fact of employment creates demand for resources. This is not a foolish position to take, but there is no end to examples of inverted price/quantity spirals that fall outside of its purview. What can happen in general happens to the specific: there can be inverted wage/employment spirals of collapsing wages and employment.

Neoclassical Growth and the Fifth Channel From Demand to Employment

In order to understand this situation we must return to fundamentals. The issue for now is under what conditions is pulling an employee out of the pool of unemployed labor a profitable investment by the hiring firm, given its portfolio of physical and financial capital. A capitalist wants to hold a contract in his portfolio when he can soundly expect to thereby obtain the fruits of the contracted labor. The four sources of unemployment can be easily understood from this perspective.

Most firms are small and illiquid, and so survival by itself demands the firm not take on labor even at a near zero money wage rate in times of high uncertainty. The fifth channel of unemployment is the uncertainty channel. Keynes goes so far as to show that expectations in the above sense determine output and employment. When this fifth channel is the operational one, it is demand which creates employment. The firm hires a laborer when it expects the demand for the increment of output to be strong and stable enough to justify the expense.

One extremely minor result which has dominated the Minsky discourse to the point I must include it is his ‘right sizing’ of the so-called neoclassical theory of growth, that is the exogenous theory of growth expounded above and its endogenous descendants. He comes to the same conclusions as his friends Samuelson and Solow: the exogenous theory of growth has stringent assumptions and can be used in the hope that some principle of continuity will preserve some of its qualitative results. Exogenous growth is, at best, a “trust but verify” fuzzy big picture view. The neoclassical theories of endogenous growth have tried to maintain the basic structure of the exogenous model while allowing some bells and whistles. The nicest thing that can be said about these models is that many of them collapse to exogenous growth theory. It’s not unusual for an endogenous growth model to exhibit endogeneity on a parameter set of measure zero.

The results of decades of endogenous neoclassical growth theory has convinced me of the truth of what Minsky predicted long ago: greater insight will mean changing not just the form of neoclassical growth theory but also the structure. We will have to open Keynes’s fifth channel of unemployment, the tension between employment and liquidity preference.

But let’s return now from the tedium of discussing economics to discussing the economy. Summarizing: the basic paradox of rationality Minsky examined is that qualitative changes in capital markets cause revaluation, switching goods from cheap to dear unpredictably. Given this, if we require all resources be in use, then the demand for resources should be unstable. Liquidity preference ‘stabilizes’ the market system by enfeebling the force of dearness so that demand is the primary actor. But, in what amounts to other words for the same thing, liquidity preference also frustrates the axiom that dearness causes plenty.

We must pick our poison. Do we let dearness exert its feeble impulse bearing dearness for a long time? Or do we take the risks involved in acting to change costs of production? Let’s go over what brought us to this impasse. In the introduction there was highminded talk about creating possibilities. The possibility of acting to lower costs of production directly in the face of long lasting dearness is how Minsky paves the way for this freedom. The last two sections went over the difficulties in achieving that freedom. Now we are set up for the practical. What we want to do with Minsky is find what can replace the feeble force of dearness to induce investment.

Part 2: Investment Rules Demand

“Keynes's theory is one in which investment is the active, driving force causing that which must be explained, fluctuations”

Hyman Minsky, JMK, Chapter 5: “The Theory Of Investment”

Yes, it is finally time to actually discuss the book under review. There are two qualitative facts about the theory of investment that must be emphasized even in a brief review like this: 1) yields are quasi-rents and 2) except for the supply schedule for capital assets and the consumption function, the investment function fluctuates wildly.

Let’s start with the first. The yield of an investment is, to some degree, a rent on the underlying asset. In other words, the yield of a capital good is not a measure of its marginal productivity as a capital good. This quasi-rent yield is why the investor might choose to hold the capital good rather than cash, a reward for ignoring his fear of goods. But still, yield is partly a reward merely for owning something. While working on this problem, Adam Smith was wise to quote Hobbes: “Wealth is power.”.

Now we turn to the second point. Starting with definitions: the supply schedule for a capital asset is its replacement cost and the consumption function which maps income(s) to consumption. The replacement cost the price of making a new capital asset as an alternative to buying one off the market. As noted in the previous section, classical economists such as Ricardo and Say concentrated on replacement costs as a part of the supply schedule to the point of exclusion. The supply schedule for a capital good is usually, both by economists and by economic actors, assumed to be stable in the short run. Recently we had an astounding exception, as the replacement cost for microchips and a range of industrial and capital equipment exploded during the COVID19 pandemic. However, this assumption isn’t theoretically all that important, for theorists or participants, and few people were surprised by the lack of an endogenous market change in chips because of it.

The stability of the consumption function is much more important and is Keynes’s contribution to economics praised even by the most anti-Keynesian. Now, filleting out the consumption function to do investment theory is the reverse of econometric practice. One normally takes investment as an input (measured by phone surveys) and tries to fit a consumption function. Milton Friedman’s most important contribution to economics by far was in estimating a consumption function in a way that found a slight effect of interest rates. Since interest rates are a relative price (the price of a forward contract divided by the price of a spot contract), this shows that consumer behavior is to some extent directed by a relative price. This was, and still is, the sole evidence for the empirical relevance of economic rationality.

The importance of this result for microeconomics only highlights the irrelevance of the form of the consumption function for macroeconomics. In a closed, balanced budget economy, aggregate demand is simply the sum of investment and consumption. Given the stability of replacement costs and consumption functions (and thereby the supply schedule for capital goods), for such an economy, to the extent demand is unpredictable it is because investment is unpredictable.

In other words, as phrased in the title of this section, it is investment that rules demand. Let us again summarize what we have seen so far, so as to illustrate the importance of this result. We want to use Minsky to create possibilities. In Minsky’s intellectual environment, there was a strong interest in the paradoxes of rationality. Qualitative economic growth itself involves such a paradox, as a company grows that company causes revaluations on its own assets. In the last section we saw how experience and theory both show we cannot rely on self-generated price fluctuation sensitive demand shifts to keep resources in employment. In this section we showed that it is investment which must make up this shortfall. This is a core part of the merely analytical side of Minsky’s economics. Now we will leave the text of Minsky for a moment to see whether Minsky and Keynes’s concerns are truly as general as they claim - can the problem of fear induced investment shortfall be simply regulated away? Or is it a fundamental part of strategic action?

Interlude: The Pure Theory Of Strategy

The reason why, when a disturbance occurs, you cannot … [precisely define the value of a capital good] any more, is because the value of the capital good depends on the present discounted value of its future earnings. The essence of the surprise is that you thought you knew what your earnings would be but it turns out that you don’t.

Robert Solow in Karen Ilse Horn’s Roads to Wisdom, Conversations with Ten Nobel Laureates in Economics

With the pure theory of strategy, we can start to cash in on the promises made in the background section. The point of going into paradoxes of rationality then and game theory now is to show that investment shortfalls are not accidental happenstances which can be swept away with one weird trick. The reason investment shortfalls are fundamental is that they are part of the uncertain strategy landscape of investment itself. One way that Minsky can be understood is by exploring the idea that market decisions are closer to so-called ‘Normal Form Trembling Hand Perfect Equilibrium’ (NFTHPE) rather than a necessarily ‘Subgame Perfect Equilibrium’ (SPE).

There are two ways to get at what I mean by this. One is to follow the literature. Hyman Minsky, Robert Solow and others have pointed out that the ‘rational expectations’ school was misnamed: RatEx economists actually often explicitly broke assumptions of rationality and besides that, assumptions like market clearing actually did more explanatory and justificatory work than expectations. But I promised in the introduction not to get into insider baseball. This is just a small note in this direction: SPE also implies much more than mere rational expectations.

It’s Time For Some Game Theory

Let’s go into what we mean by our strategy concepts. We will start with NFTHPE. has three parts: Normal Form (NF), Trembling Hand (TH) and Perfect Equilibrium (PE).

Normal Form means that we list all possible strategies for each agent and the payoffs that are the product of each combination of possible strategies.

This normal form tends to hide the sequential structure of strategy. In this case, we aim to leverage this rather than bemoan it.

Trembling Hand means that agents act as if there is a non-zero chance they may use any feasible strategy in the future.

Thus to the extent an agent can control themselves they put as much weight on playing any best response strategy they can. As their level of control rises, they put more effort into the bests of the best response strategies.

Perfect Equilibrium means that the strategies played are in all trembling hand strategies.

To put it informally, they are the actions of those who do have control who are aware they might not have perfect control.

Before moving on, we can build a little intuition. If a best response gives a non-zero chance to all strategies - a la Rock, Paper Scissors - then it is automatically a NFTHPE. If the best choice is to tremble, then just do it. The basic intuition of the NFTHPE can be put something like this: “More control should never make you worse off - if randomness works better, then choose randomness.”.

Contrariwise, an SPE is more like an extension of Tic-Tac-Toe than Rock, Paper, Scissors. The main point of Tic-Tac-Toe is to place your symbol in a place such that whatever your opponent does, you don’t regret placing it there. For an SPE in general, control is assumed and avoiding regret is the only consideration. As a result, an SPE oriented agent often cannot take advantage of an opportunity. To paraphrase EEC Van Damme’s Refinements Of The Nash Equilibrium Concept, an SPE oriented agent is restricted to act as if his a priori expected payoff was true, even if the world and other agents act completely differently than that suggests. In other words, an SPE oriented agent never expects qualitative change.

What are the implications for financial strategies? One is that because finance is more like an NFTHPE is not a SPE, so-called ‘non-credible’ threats and even strictly dominated strategies can matter. The concept of ‘non-credibility’ assumes that the agent’s a priori expectations of credibility are stationary. Financial agents do not act as if their a priori expectation will hold true come what may. They can revise whether they think a threat is credible or not on the fly. This makes the job of the financier - whether a central banker or an ordinary individual - harder. They have to care not only about how their fellow actors revise their ex post expectations, but also have to plan for the whole market ecology to shift as actors revise their revisions. This finally brings us to the last link in the Minsky’s chain, the method by which actors can plan for their a priori evaluations to be wrong.

Part 3: Liquidity Opens Strategy

“Rational agents know that they do not know. The assumptions underlying the models of investment and portfolio choice that lead to the Keynesian concept of liquidity preference are that the agent recognizes their own fallibility and that, as a result, that events deviating from from what a maintained model indicates as outcomes will lead to revisions in the maintained model that in turn can change behavior.”

Hyman Minsky, ‘On The Non-Neutrality Of Money’

In order to have access to a wide variety of strategies, economic agents hold so-called “liquid” assets. “Liquidity is”, as Ken Boulding says in “Implications For General Economics Of More Realistic Theories Of The Firm”, “a measure of the degree of perfection of the market for an asset; i.e., the extent to which it can be exchanged for any other asset in indefinite quantities without loss due to worsening terms of trade.”. By holding assets of relative liquidity, a firm or household enables itself to abandon course when revising beliefs.

Now, the liquidity of an asset is not an a priori fact about that asset, it is anterior to market behavior. And yet, it is access to liquidity which is the sole justification for the ancient social practice of marketing. A market gives some actors (not enough) some access (not enough) to a form of certainty which opens possibilities. Markets are just places where liquidity happens.

The ‘openness’ of liquidity leads to Minsky’s famous “two price levels”:

The price level of financial assets whose prices move fluidly

The price level of physical outputs whose prices slowly

Starting with the second price level, one can see that short run strategies around markets for physical outputs are practically limited to threats involving moving/creating financial assets. Source: every page of the FT every day. Many of these threats are not credible, but become credible.

For instance, a monopolist can hold liquid assets and threaten to lower prices against a potential competitor. If the monopolist doesn’t hold enough liquid assets to bankrupt a potential entrant, the entrant may regard the threat as noncredible. As the entrant sees the monopolist take on debt to raise the funds to survive a period of low prices, the threat becomes credible. The current monopolist has an advantage over the potential entrant via a principle of increasing risk which was not part of the a priori evaluation. Monopolies supporting themselves through manipulating liquidity instead of producing product is, in essence, the financialization crisis thesis.

Liquidity Opens Strategy; Unknowledge Closes It

There is a dual to the title of this section: unknowledge closes strategy. In Samuel Bowles’ Microeconomics, a “risk dominant equilibrium” is defined to be the best strategies assuming other agents act randomly. Risk dominant strategies are rarely payoff dominant, which Bowles uses as a model for development traps. It is hard for laborers in Palanpur, Bowles claims, to trust their neighbors to plant earlier in the year. That strategy is thus closed to them (although Hirschman might, and probably more truly, see this as an opportunity for growth than as a growth-preventing trap).

Let’s return to the example of financialization, Minsky would note that a monopolist taking on debt to fend off entrants is actually a losing strategy over time. Every time the monopolist has to fend off a potential entrant they trade their old position for the same position but with more debt. In fact, in the long run, only debt that changes the position of the debtor is stable. Manipulating liquid assets to fend off competition risks rather than investing is what Minsky calls hedge borrowing. Eventually, the monopolist’s position may worsen to the point that its illiquid assets are in hock to continue the competition risk games. This is what Minsky calls Ponzi finance.

Now, laugh, friends, the comedy is over! Let us take the time to integrate over our progress. In our strange interlude I propounded the idea that financial agents are like trembling hand actors in a game - they like control but not because they assume their a priori expectations will be stable. This fed into the idea of liquidity as a source of financial agency. Once we see that it is liquidity that opens up the field to radical belief revision, we check liquidity’s effect on investment. Playing games with liquidity to keep one’s position is unstable because it leads to Ponzi finance. Liquidity’s essence is freedom and she will not be mocked long. This leads to instability in investment as qualitative changes force market wide revaluations. Instability of investment is itself instability in demand. Without stable demand, the ability of dearness to defeat dearness is enfeebled. There is a systemic and essential weakness in the traditional price oriented program.

What is the solution? One is to reduce uncertainty by shifting to a design framework. Once this framework is outlined, the process of achieving that framework is through creating and using liquidity to strengthen the power of competition and the adaptability of firms and households. Minsky is, as argued in the introduction, the prophet of the designer economy:

“In a design framework, economic policy focuses on constructing and reaching a specifically envisioned future. This is different from traditional industrial strategy: It doesn’t “pick winners,” but rather pushes government agencies to have a broad awareness of technological and economic trends in order to promote specific potentialities. In contrast to planned economies or developmental states, a Designer Economy’s primary focus is on a dynamically changing future, and it aims to produce tools to enable various actors in the economy to adapt to these changes in a matter that preserves the public’s preferences through iterative experimentation.”

“The Designer Economy”, Yakov Feygin & Nils Gilman

Conclusions

“congratulations, you just invented Hyman Minsky.”

All of the above only scratches the surface of Minsky’s JMK, which is only one part of his system of thought. I haven’t covered his detailed algebraic models or his historical work. Having reviewed at least some small part which is actually in Minsky, I will be more speculative and less pedagogical in this conclusion.

In my opinion, Minsky’s ‘Two Price’ system is a rational generalization of ‘money’ in the neoclassical system. Recall Yap, the well known island of stone money. Their economic culture was admired by neoclassical economist Milton Friedman. What is it that Friedman is admiring? It is that the Yap people have a payment system.

“Acheter, c’est vendre et vendre, c’est acheter” Bagehot quoted Quesnay with approval. This is still taken as axiomatic by economic models today. But most trade is not barter. Most trade takes place through the plumbing of a payment system. How did that happen?

To put it another way, Minskyians often say anyone can invent a currency, the trick is to get someone to accept it. To go back to David K Lewis - who seemed so far out at first - how can an actor introduce a new signal which actually shifts the behavior of those receiving it? Can you take a phrase that’s rarely heard, flip it and make it a daily word?

Coming back to economics, Fisher’s circular flow with a meaningful velocity is a simplified payment system without checks, letters of credit, commercial bills or anything but gold coins really. A price then becomes a simple signal s in a Lewisian game.

Minsky’s generalization - and, as he says, Keynes’ generalization before him - is to replace Fisher’s “velocity of money” with a more realistic portfolio theory of finance. This is an extensive change - the Keynesian Revolution - because for Minsky the portfolio is the active part of the economy but for Fisher the velocity of money is a passive part of the economy. In essence, the duality between signal and action is blurred.

The majority of post-Minsky research has been towards continuing this rational generalization towards denser theories of the plumbing of the financial system. This isn’t bad per se but this research misses the important growth aspects of Minsky. In particular, Minsky’s system is a rational generalization - a ‘general theory’, as it were - of neoclassical economics of both growth and the business cycle without the crutch of so-called ‘natural values’, such as the infamous ‘natural interest rate’ of Wicksellian monetary theory.

A natural value in general is a relative price which satisfies additional relations to the typical market relations seen in economics. For instance, an actual interest rate - being the relative price of a spot vs forward - satisfies certain market relations. Contrariwise, the ‘natural interest rate’ is an almost mystical relative price which would bring an end to net intermarket money flows, even those into the money market or those meant to bankroll production (“real bills”).

These natural rates dominate narratives of economic dynamics. Natural rates are so popular because they seem to give meaning to the non-market idea of a relative price being “too low” or “too high”. However natural rates are unnecessary if, like Minsky and Keynes, we use intelligently chosen national accounts.

For instance, if the Federal Reserve thinks - as it says - millions of people need to be unemployed in order for the economy to stabilize, then it should be questioned of what sectors should this unemployment come from?

This question is obfuscated by changing it to which sectors are being paid above their ‘natural wage’. The obvious difficulty is that the natural values are subject to change during qualitative growth periods. Thus they fail to guide us in exactly the case when we need them.

Even this relatively simple point demonstrates how Minsky’s Keynes gives us a simple and rigorous market oriented economics.

What does mean 'to the point of exclusion'??? in below statement. I do not recall anything like that in Ricardo or Say, where is that to be found? '.....classical economists such as Ricardo and Say concentrated on replacement costs as a part of the supply schedule to the point of exclusion.'