Review Of Anna Carabelli’s “Keynes On Uncertainty And Tragic Happiness”

Against Not Reading Keynes

“The connexity and continuity of economic elements … are the chief grounds of difficulty.” - Keynes, Alfred Marshall

Today, we are going to be asking a number of questions, all of which center around the core question “Why read Keynes at all?” Since economics often figures itself as a scientific, rather than literary, discipline, contemporary practitioners often have little interest in how or why the tools which are now efficacious came to be. This disinterest gets us quickly into one of the core tensions in Keynes’ work, as I pointed out in The Liberal Logic Of Uncertainty From 1320 To 1974: “Is philosophy about forming a Socratic dialectic with one’s cultural endowment or about sharply defined intuition gadgets?”

Anna Carabelli, as a lifelong mapper of this borderline within Keynes’ thought, will help us give an interesting answer to this and other questions. We will be talking about her most recent book, Keynes on Uncertainty And Tragic Happiness: Complexity And Expectations, which was released on the 100th anniversary of the publication of Keynes’ Treatise On Probability. Where her contemporaries avoided giving Probability a proper reading on the - likely true - grounds that they were not sufficiently versed in abstract logic to follow the Keynes/Russell debates, Carabelli has consistently and masterfully showed how those fundamental logical concepts inform Keynes’ economic methodology.

On Reading Keynes

To answer the question “Why read Keynes at all?” we have to have some sense of what we are reading him for. As the legacy of disagreements on both the policy and theoretical level makes clear, there is rarely a clear and distinct linkage between what Keynes wrote, and what gets called “Keynesian,” let alone “Keynesianism.” But Carabelli’s work presents us with a more basic problem: Was Keynes the last great economist to be a great philosopher or the last great philosopher to be a great economist?

Carabelli takes the latter fork, emphasizing for the last 34 years that Keynes’ doctrines were always a logical working out of his basic philosophical insights. If we read Keynes to read him as a philosopher, we have two obvious comparisons for his strange reputation of readability and density: Hegel & Nietzsche.

Reading Hegel, it is borderline impossible to understand a sentence of Phenomenology Of Spirit, but it’s easy to give a general picture of the gist.Nietzsche is the opposite: as we know from Blazing Saddles, every sentence of Thus Spoke Zarathrustra is a masterpiece of quotability, but it’s borderline impossible to give the gist of the general picture.

Keynes, unfortunately but instructively, is neither. People use his most quotable lines every day – “Animal Spirits”, “Magneto Trouble”, “In the long run we are all dead”, “Normal Backwardation” – while at the same time writing no end of synoptic summaries.

The difficulty here is not that the parts are unclear, or that the whole is too convoluted. Instead, the difficulty is in building anything mesoscale: something bigger than glib out of context quotes but smaller than a universe. In this way, the difficulty involved in reading Keynes is closest to the difficulty involved in reading Leibniz.

Reading Keynes, then, requires a “rare combination of gifts”: the philosophical acuity to discern the light of the general out of the canvas of the specific and the patience to carefully examine each fine detail in turn. Metaphorically, this is much like in stellar spectroscopy, where one must have a telescope to see the star and a microscope to reveal the multiplet fine structure.

Interpreting Keynes requires these gifts because Keynes writes with an awareness that, to paraphrase Kołakowski in Husserl And The Search For Certitude, abstraction is never of interest unless it is applied abstraction. The reader, therefore, must always be careful to discern what is essential from what is accidental. It is the accidental which adds muscle to the skeleton of the essential, ensuring the intellectual structure remains limber, while the essential provides something fixed against which the specificity of the accidental can push. Building a theoretical body in this way requires both structure and form.

And so differing interpretations abound. Slight changes in logical force, say, shifting a single sentence fragment across the line from “accidental” to “essential,” results in an entirely new reading.

Thankfully, we don’t have to bring out tales of the mighty dead to illustrate this difficulty in interpreting Keynes. We can instead compare two relatively recent readings of Chapter 12 of the General Theory.

For geographer Paul Krugman, the irrationalism involved in investment is essential: “[Chapter 12’s] essential message is that investment decisions must be made in the face of radical uncertainty to which there is no rational answer, and that the conventions men use to pretend that they know what they are doing are subject to occasional drastic revisions, giving rise to economic instability.”. In other words, the essential sentence for Krugman is: “Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as a result of animal spirits — of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.”.

Compare this to CVAR founding editor Alex Williams’ rationalist reading: “To get rid of uncertainty, you have to know more about what the future will bring, so as to be able to invest in it successfully. … To get rid of illiquidity in capital goods for the economy as a whole, you need to figure out how to instantly transmogrify some capital goods into other capital goods. … if neither of these roadblocks can be totally eliminated, what can you do? … [Create] something like a stock market, where ownership of big investments can be parceled out into little pieces [which] makes any given investment liquid to any given owner. If something goes wrong with it, they can dump their shares and move on with life, rather than live on as the ruined owner of a failed bakery…”. This takes as the essential passage “We should not conclude from this that everything depends on waves of irrational psychology. On the contrary, the state of long-term expectation is often steady, and, even when it is not, the other factors exert their compensating effects.”

The interpretive choices one makes are not arbitrary–how one interprets Keynes’ work always has to do with one’s general intellectual orientation. Krugman’s irrationalist reading is transactions-oriented: if transactions are largely the result of animal spirits, then it immediately follows, in Krugman’s introduction, that the state of long term expectation is irrational. Williams’ rationalist reading is market structure-oriented thinking - social institutions cannot survive if they depend too much on investors being not stupid.

How much heft there is in Keynes’ writing! A single interpretive difference between two readings of section seven of chapter 12 of book four reveals both Keynes’ multiplet structure, and the social orientation of two readers.

Finally, we are ready to examine the work of one of his best readers: Anna Carabelli

On Reading Carabelli

Carabelli sees Keynes as a philosopher with a consistent method and logic, progressively explicated and refined from one book to the next. She is so obviously correct on this point that the only sensical reason to still believe the General Theory represented a massive break is the simple momentum of old ideas.

Her book gives three spectral lines, three approaches to understanding Keynes’ programme as a whole: Keynes As Moral Scientist, Keynes As Logician Of Risk & Uncertainty and Keynes As Economist. We will explore each of these in turn.

Keynes As Moral Scientist

If you have ever taken an Intro to Ethics course, you will likely be familiar with the three reductive typologies:Consequentialist, Deontological and Virtue.

Consequentialist ethics imagines the world into an actor who performs conduct and experiences consequences. The valuation of the consequences is the sole method of ethical justification of conduct.

Paradigm example: Utilitarianism

Modern example: LessWrong

Deontological ethics examines moral language into ‘maxims’. An ethical maxim is distinctive from a useful maxim only because of its special logical substructure.

Paradigm example: Kant

Modern example: Francis Fukuyama

Virtue ethics examines the halo of complex objects to judge whether the object is itself good in some relevant sense. An object exemplifies a kind of goodness in the way a ball exemplifies a kind of roundness.

Paradigm example: Plato

Modern example: Alasdair McIntyre

For Carabelli, Keynes is a virtue ethical pluralist, like Aristotle or Isaiah Berlin, as we can see in some block quotes:

“The attributes which belong to states of affairs and not, in every case, to states of mind in isolation are those which are suggested by the words - Beauty, harmony, Justice, tragedy, Virtue, Consistency, truth - or by their opposite....In a similar way, a state of affairs may be tragic and, therefore, not to be desired, although the feelings of the actors in it may be all noble and heroic.”

Keynes, On The Principle Of Organic Unity

“But is the obligation to do good? Is it not rather to be good?”

Keynes, Egoism

Carabelli argues that this ethical orientation fundamentally structures Keynes’ understanding of the micro-macro relation, and the strategies he employs to connect the two sides. Even if we imagine every individual transaction between a firm and laborers to be ‘noble and heroic,’ the outcome, and even the system itself can prove tragic. That the noblest of intentions – even the noblest of actions – on an individual level may ultimately prove tragic when viewed in the context of the system as a whole is the philosophical base which later, less sophisticated approaches to macroeconomics rejected.

This non-additivity between microeconomic action and macroeconomic fact is central to Carabelli’s reading. To illustrate this point, she delves deeply into the impact of his analysis of Troades by Euripides on his development as a psychologist and ethicist:

“For, instance, persons, in such situations as we call tragic, may I think be at the same happy in the sense I am suggesting. When at the end of the Troades, despite and through the overwhelming horror of her situation Hecuba suddenly realises the splendour of her own tragedy, she is happy.” Keynes, Virtue And Happiness.

Keynes interprets Hecuba’s burial of Astyanax as an act of noble heroism parallel to Antigone’s burial of her father and brother. As I see it, this interpretation invites comparison to three essays by his rough contemporaries: Nietzsche’s Die Gerburt Der Tragödie, Albert Camus’s Le Mythe De Sisyphe and Horkheimer & Adorno’s Dialektik Der Aufklärung.

Die Gerburt Der Tragödie

In this book, Nietzsche rejects Winckelmann’s famous premise that the Greeks had it all figured out, that Ancient Greece was a happy, innocent and rational society. Nietzsche argues that, despite the nobility of the attempt to capture the music of Hecuba’s suffering, Euripidies was too weighed down by philosophy (he politely leaves the “like me” implicit):

“Euripides fühlte sich - das ist die Lösung des eben dargestellten Räthsels - als Dichter wohl über die Masse, nicht aber über, zwei seiner Zuschauer erhaben: die Masse brachte er auf die Bühne, jene beiden Zuschauer verehrte er als die allein urtheilsfähigen Richter und Meister aller seiner Kunst…Von diesen beiden Zuschauern ist der eine - Euripides selbst, Euripides als Denker, nicht als Dichter. Von ihm könnte man sagen, dass die ausserordentliche Fülle seines kritischen Talentes, ähnlich wie bei Lessing, einen productiv künstlerischen Nebentrieb wenn nicht erzeugt, so doch fortwährend befruchtet habe… Das Wunderbare war geschehn: als der Dichter widerrief, hatte bereits seine Tendenz gesiegt. Dionysus war bereits von der tragischen Bühne verscheucht und zwar durch eine aus Euripides redende dämonische Macht. Auch Euripides war in gewissem Sinne nur Maske: die Gottheit, die aus ihm redete, war nicht Dionysus, auch nicht Apollo, sondern ein ganz neugeborner Dämon, genannt Sokrates.”

Instead of imagining Hecuba (as a philosophical personage) happy the way the young Keynes suggests, the young Nietzsche demands that we create a new music able to capture and release the sadness of a real (i.e. continuous) person.

As Nietzsche would later explain in ‘Versuch einer Selbstkritik,’ Keynes’ analysis of Hecuba is superior: Wagner’s alternative to Socrates “die Kunst - und nicht die Moral - als die eigentlich metaphysische Thätigkeit des Menschen hingestellt” is an unacceptable form of consequentialism. The French decadents go on to show how quickly this kind of Wagnerism devolves into nihilism with little to recommend it beyond the workmanship of the decor and the quality of the wine. Only later, with “Zarathustra der Tänzer” could Nietzsche find a consistent virtue ethic to be ironic about.

Le Mythe De Sisyphe

“Toute la joie silencieuse de Sisyphe est là. Son destin lui appartient. Son rocher est sa chose. De même, l’homme absurde, quand il contemple son tourment, fait taire toutes les idoles… Je laisse Sisyphe au bas de la montagne! On retrouve toujours son fardeau. Mais Sisyphe enseigne la fidélité supérieure qui nie les dieux et soulève les rochers. Lui aussi juge que tout est bien. Cet univers désormais sans maître ne lui paraît ni stérile ni futile. Chacun des grains de cette pierre, chaque éclat minéral de cette montagne pleine de nuit, à lui seul, forme un monde. La lutte elle-même vers les sommets suffit à remplir un cœur d’homme. Il faut imaginer Sisyphe heureux.”

In general, Camus’s Sisyphus is just the parts of Also Sprach Zarathrustra that directly relate to eternal recurrence, Sisyphus’ mountain in the above quote is, of course, really Zarathrustra’s mountain. However, in Also Sprach Zarathrustra, recurrence starts as dramatic irony: we know from the beginning Zarathrustra is in a cycle but he does not. Camus, by contrast, provides no irony. Sisyphus knows already that his task is impossible - he “contemple son tourment”.

Camus doesn’t mention that Socrates, the master of irony, may have believed philosophy could free Sisyphus. This possibility points to why I believe Keynes’ analysis of Hecuba is superior to Camus’ analysis of Sisyphus. It is easy to say that Hecuba burying her child is absurd - Astyanax stays dead no matter what happens – but that statement transforms nothing of the situation. By instead emphasizing the tragic nobility of her spirit, Keynes gives Hecuba’s actions real weight.

Dialektik Der Aufklärung

In Horkheimer & Adorno’s book we find the claim the vile Citizen Sade straightforwardly represents the bourgeois ideal: the philosopher as sadist. The scientist, they say, knows the earth to the extent that he can make her submit: her “an sich” becomes “Für mich”. Being less of a literary masterpiece than the works above, I will provide excerpts in translation:

“Sade and Nietzsche knew that their doctrine of the sinfulness of pity was an old bourgeois heritage. The latter speaks of ‘strong times’ and ‘aristocratic cultures’, while the former refers to Aristotle and the Peripatetics.”

“In Sade as in Mandeville, private vices are the anticipatory historiography of public virtues in the totalitarian era.”

Whatever the flaws in the book, the question of whether imagining Hecuba happy is a species of Justineism - the darkest form of sadism - still remains. Why is it that imagining Hecuba happy does not require us to be sympathetic to the child murderer Odysseus? For an answer, we need to go deeper into Keynes’ logic.

Keynes As Logician Of Risk & Uncertainty

A philosopher must be more than interpretive: a philosopher must have a logic. Carabelli has long been concerned to show exactly how Keynes’ approach to risk & uncertainty, his primary interest, is an essentially logical one.Unfortunately, Keynes’ approach to logic is too complicated to go into here. Besides, that’s the subject of On Keynes’s Method, not Keynes on Uncertainty And Tragic Happiness.I would summarize the part of Carabelli’s telling which is relevant here by oversimplifying Keynes approach into a distinction between two logical operations named after operations in arithmetic: sums and products.

The primary fact about a product is that a product is as complex as a pair of factors. More precisely, a product is a way of combining a pair of objects such that the output can be factored back into the input. So for instance, 85 can only be factored in one way and so is called the product of 17 and 5. A sum, meanwhile, is only as complex as one of the summands. Sums are therefore harder to define precisely, but loosely speaking a sum is approximately a relation between three objects such that if two are fixed then so is the third. For instance, x+y=85. For any choice of x, then y is fixed as 85-x. Due to the magic of category theory, the names product and sum are far more than analogies.

There are pure sum approaches to economics. For instance, monetarism attempts to give a dynamic reading to the equation of exchange by interpreting it as the pinning together of one gargantuan aggregate money flow. There are also pure product approaches, such as game theory. This attempts to understand the economy as unboundedly multilateral monopolies and monopsonies by specifying every possible action the actors can take and the determinant outcomes of those actions. These are prone to exactly dual pathologies: aggregation and disaggregation to the point of literal meaninglessness, respectively.

The almost exceptionless rule in economics is that economic systems are “complex”. Units whose coherence must be retained by a product interact through sums. Thus almost all practical reasoning generally requires one to use both products and sums, and to use each only for its fit purpose.

That said, summing does the lion’s share of the work as it reduces complexity. Sums must be homogeneous, thus the emphasis on The Choice Of Units. Keynes frequently emphasizes that structural similarity, such as found between different applications of probability, is not sufficient for summability:

“If the barometer is high, but the clouds are black, it is not always rational that one should prevail over the other in our minds, or even that we should balance them, - though it will be rational to allow caprice to determine us and to waste no time on the debate” - Treatise On Probability, Part I, Chapter III: The Measurement Of Probabilities.

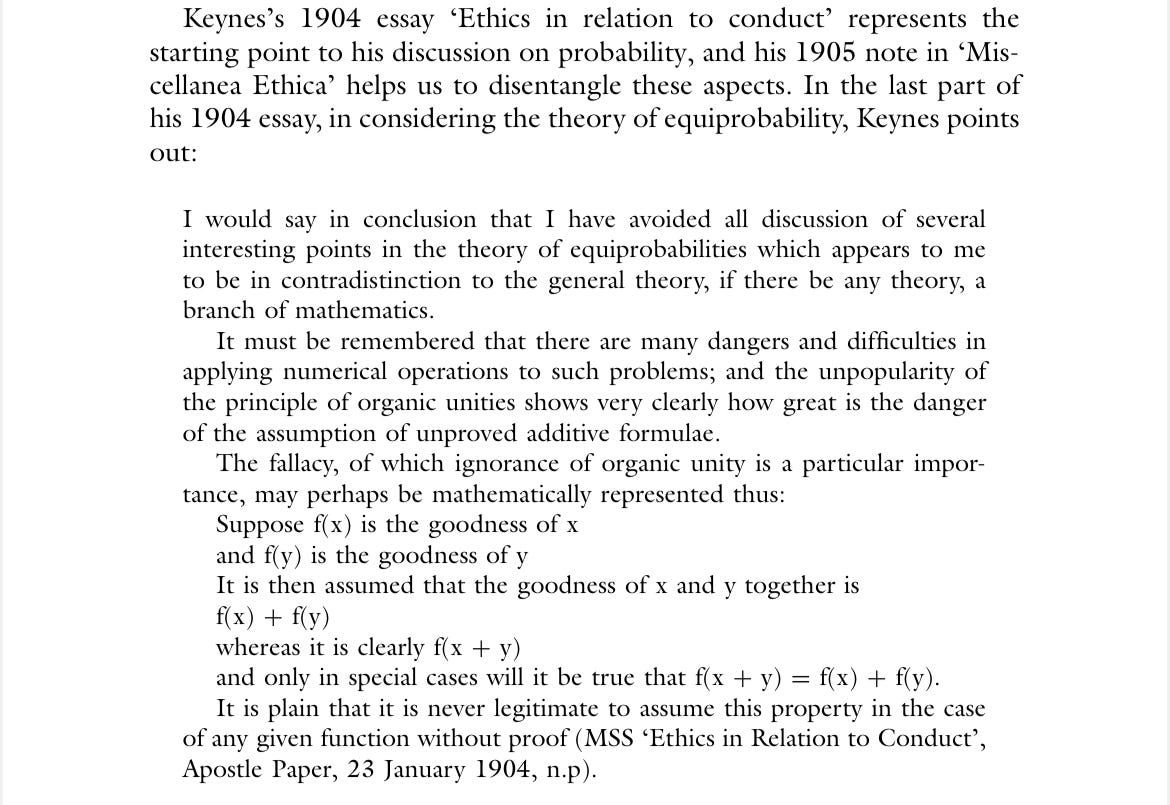

Carabelli demonstrates that this ‘organic interdependence’ was a concern of Keynes from his earliest writings. This demonstration is so nice that I feel I must include it whole:

This kind of “mathematics” conveniently explains how Keynes’ analysis of Hecuba avoids the trap laid by Horkheimer and Adorno. Let x be Hecuba’s noble state of mind in giving Astyanax a proper burial and y be the death of Astyanax. The mistake is in valuing the situation by adding the value of Hecuba’s mental state to the (negative) value of Astyanax’s death. Instead, Keynes points out that the situation can only be valued as a whole, because Hecuba’s mental state and Astyanax’s death are mutually interdependent. Adorno needs to claim that since f(x+y)>0, the bourgeois secretly believes f(y)>0 and thus is Sadean. Per Keynes, this is a non sequitur.

A natural, if surprising, contrast to Keynes logic can be seen in Paul Davidson’s “non ergodic systems” approach.

First off, a bit of technical background on what “ergodic” and “non-ergodic” mean mathematically. In the case of finitely many “states”, a system is ‘ergodic’ only if the matrix of probabilities of going from state i to j is irreducible and aperiodic. This would be true if, for instance, there was a non zero probability of going between any two states in one step.

However, we are far more interested here in the intuition and theory structure than the exact maths. In that sense we can use a slightly less abstruse phrasing. The basic intuition is that the outcome-space of an “ergodic” system is “closed” in a meaningful, if difficult to observe, sense.

As Carabelli explains, Davidson’s theory is ontological rather than logical: it begins by presuming that there are things called ‘states of the world,’ and things which are ‘probabilities of transitions between states’ which relate them.

Davidson refers, according to Carabelli, to the pure frequentism of the Moscow School Of Probability (See Mathematics: Its Content, Methods And Meaning, Book 2, Chapter XI, section 4: Further Remarks On The Basic Concepts Of The Theory Of Probability for more).

Carabelli argues rightly that the Moscow School is largely irrelevant to Keynes. But its complete irrelevance is not so clear. In Marshall’s Tendencies, John Sutton makes the point that Marshall’s understanding of the laws of economics is in fact closely related to the exact kind of complex dynamic problem which Kolmogorov et.al. were working on. From Principles Of Economics, Book I, Chapter III: Economic Generalizations Or Laws:

“But let us look at a science less exact than astronomy. The science of the tides explains how the tide rises and falls twice a day under the action of the sun and the moon: how there are strong tides at new and full moon, and weak tides at the moon's first and third quarter; and how the tide running up into a closed channel, like that of the Severn, will be very high; and so on. Thus, having studied the lie of the land and the water all round the British isles, people can calculate beforehand when the tide will probably be at its highest on any day at London Bridge or at Gloucester; and how high it will be there. They have to use the word probably, which the astronomers do not need to use when talking about the eclipses of Jupiter's satellites. For, though many forces act upon Jupiter and his satellites, each one of them acts in a definite manner which can be predicted beforehand: but no one knows enough about the weather to be able to say beforehand how it will act. A heavy downpour of rain in the upper Thames valley, or a strong north-east wind in the German Ocean, may make the tides at London Bridge differ a good deal from what had been expected.

The laws of economics are to be compared with the laws of the tides, rather than with the simple and exact law of gravitation”

Leaving aside the differences in scale between astronomy and the tides, and the difficulty of micro-macro interrelation, there is a tension here. In a presentation, Carabelli used Keynes’ high barometer and low clouds example to make exactly this point. This is not an altogether happy choice though, as the weather is largely well approximated by the kind of dynamical systems that interested the Moscow School. Indeed, progress in weather forecasting has been due to increasing computational power rather than greater logical specification a la Keynes.

In my opinion, a better example would be the so-called Mpemba Effect, the ability of hotter liquids to freeze more rapidly than cooler liquids. There is, in fact, no “Mpemba Effect”, in the sense that there is no unitary cause which forces the hotter liquid to freeze faster. The discovery is really that of the falseness of the “Anti-Mpemba Fallacy”: which we could posit as the idea that “the hotter liquid is moving through the same states the cooler liquid started at” and thus the hotter liquid must freeze later as long as the freezer is the same temperature. Accordingly, the core part of this research is not measuring the scale or unity of a cause, but of phrasing a claim correctly. This is a logical rather than arithmetical problem, but sorting this pedantic example is beginning to take us too far from Keynes.

Keynes As Economist

In the penultimate chapter of Keynes on Uncertainty And Tragic Happiness Carabelli synthesizes all of Keynes’ writing on international economics from 1913-1945 to show the unity of his method and how the applications flow from the philosophical positions sketched above.

This is the happiest chapter in the book, as one can easily find Keynes simply discussing the exact philosophical positions Carabelli is unfurling. Indian Currency And Finance ends with a note on the organic interdependence of financial systems much like that of “Ethics In Relation To Conduct” above. Then there is this famous depiction of a comic tragedy, dual to a tragic happiness:

“Paris was a nightmare, and every one there was morbid. A sense of impending catastrophe overhung the frivolous scene; the futility and smallness of man before the great events confronting him; the mingled significance and unreality of the decisions; levity, blindness, insolence, confused cries from without,—all the elements of ancient tragedy were there. Seated indeed amid the theatrical trappings of the French Saloons of State, one could wonder if the extraordinary visages of Wilson and of Clemenceau, with their fixed hue and unchanging characterization, were really faces at all and not the tragi-comic masks of some strange drama or puppet-show.”

Economic Consequences Of The Peace

Carabelli then develops a reading of General Theory which places great importance on Book VI, chapter 23: Notes On Mercantilism. The reason is obvious: this chapter is the obvious first step to her goal of showing how Keynes philosophical analysis is worked out in his work on international trade.

Keynes defines mercantilism as the doctrine that there is a “peculiar advantage to a country in a favourable balance of trade, and grave danger in an unfavourable balance, particularly if it results in an efflux of the precious metals.” Mercantilism therefore obviously fails the simplest test of summability - there’s no way everyone’s balance of trade can be positive. However, Keynes argued that the obviousness of this failure has unfortunately blinded many economists to the merits of the arguments behind them. Classical economists have, in fact, been blinded by their habit of accounting in terms of value, ignoring that firms have preferences over how much of their value is held in different stocks.

Taking Boulding’s Market Equation as a guide, we can see the logic simply. An efflux of currency then necessitates a reduction in price, liquidity preference or illiquid good stock, all of which are code words for social ills: deflation, financial instability and industrial instability respectively. An absorption of goods is exactly symmetric to an efflux of currency, thus the protectionism of mercantilism.

Keynes goal then is creating a “twice blessed” system that can actually capture the social stability identified by the mercantilists without their impossible-in-general policy recommendations. Only a mix of sums and products can find a system of organic interdependence in which individual households, firms and nations have the flexibility they need to thrive.

The essential economic issue raised by Keynes is the summability of liquid money vs the unsummability of illiquid assets. This creates a ‘fear of goods’ symmetric to the ‘love of money,’ and introduces an affective dimension into the circulation of M-C-M’ that even Freudo-Marxists often miss. Keynes had, in fact, been dealing with this symmetry since he beginning work as an economist. In Dr Melchior: A Defeated Enemy, Keynes gives an almost Freudian depiction of this fear in relation to Versaille.

So one of the running goals through Keynes’ political life was to create an international economic system which balanced the needs of individual economies to remain individual factors in the global economic organism with the need of the financial stock to sum up across all of them. Carabelli summarizes in this graph:

Carabelli’s reading differs from Skidelsky’s reading, who sees the elderly Keynes as doing a kind of (admirable) advocacy for the UK. The questions between Carabelli and Skidelsky on the older Keynes can be separated into two parts:

Is Keynes’ international economic proposals a kind of mercantilism?

Carabelli describes Keynes policies as a kind of “mercantilist flavored” “embedded liberalism”, that is to say, a liberalism in the sense of allowing the actors to make their own decisions.

She contrasts this with Merkel mercantilism’s “unembedded liberalism”, a ‘liberalism’ of taking away decisions.

Is Keynes a kind of nationalist?

Keynes is, I would say, a Hecuban nationalist. That is to say, a nationalist who is capable of burying the innocent war dead without finding scapegoats.

This contrasts with fascistic nationalism, in which, by definition, the pure people cannot fail so that a scapegoat must always be found to explain away tragedy.

Conclusion

The multiplet structure of Keynes and his system has, I think, been amply shown by the degree of shading required to answer questions like “Is Keynes a mercantilist or a free trader?” or “Is Keynes a nationalist or a cosmopolitan?”. One could add “Is Keynes a socialist or a liberal?” and many, many others to this list.

Doing economics with a heavy emphasis on keeping track of both products and sums requires an attentive tool user. And yet, despite this complexity, Keynes is the inventor of macroeconomics: not his contemporaries Tinbergen, Frisch or Harbeler. Why was this?

The reason is clear even to Paul Krugman. Keynes was the first who understood that economic methods had to answer the questions of the complex total economy.

Unfortunately, "Contemporary Macroeconomics" denotes an academic discipline which has access to Keynes’ particular tools - the choice of units sufficient to give external validity of summation, etc. - but no longer has the interior validity to structure uses of those tools into a consistent method.

Keynes’ special place in the history of thought can be illustrated by a simple contrast. Nietzsche & Camus were concerned with the internal validity of the individual good life: with Zarathrustra’s lonely path through the eternal recurrence. Hegel and his modern followers - most importantly Francis Fukuyama - are, by contrast, interested in the internal validity of the collective good life. Modern utilitarian economists like J Bradford DeLong use methods descended from the work of Tinbergen to satisfy their interest in the external validity in the collective good life.

By contrast with all of the above, Keynes is interested in how external validity - the divinely ordained war of Hellas and Illios - can stand in contrariety with the internal good life - Hecuba’s nobility. It is just our luck that his doing so involved the development of tools, and not just narratives, such that we might try to live together a little better.

In sum, Keynes’ tools for understanding the intrinsically complex social world are themselves intrinsically complex because he takes seriously the possibility and even reality of tragic happiness. The answer to “why read Keynes” is simple: he is useful!