Lun Yu 1.12 & 13

Lesser Virtues

Chapter 1

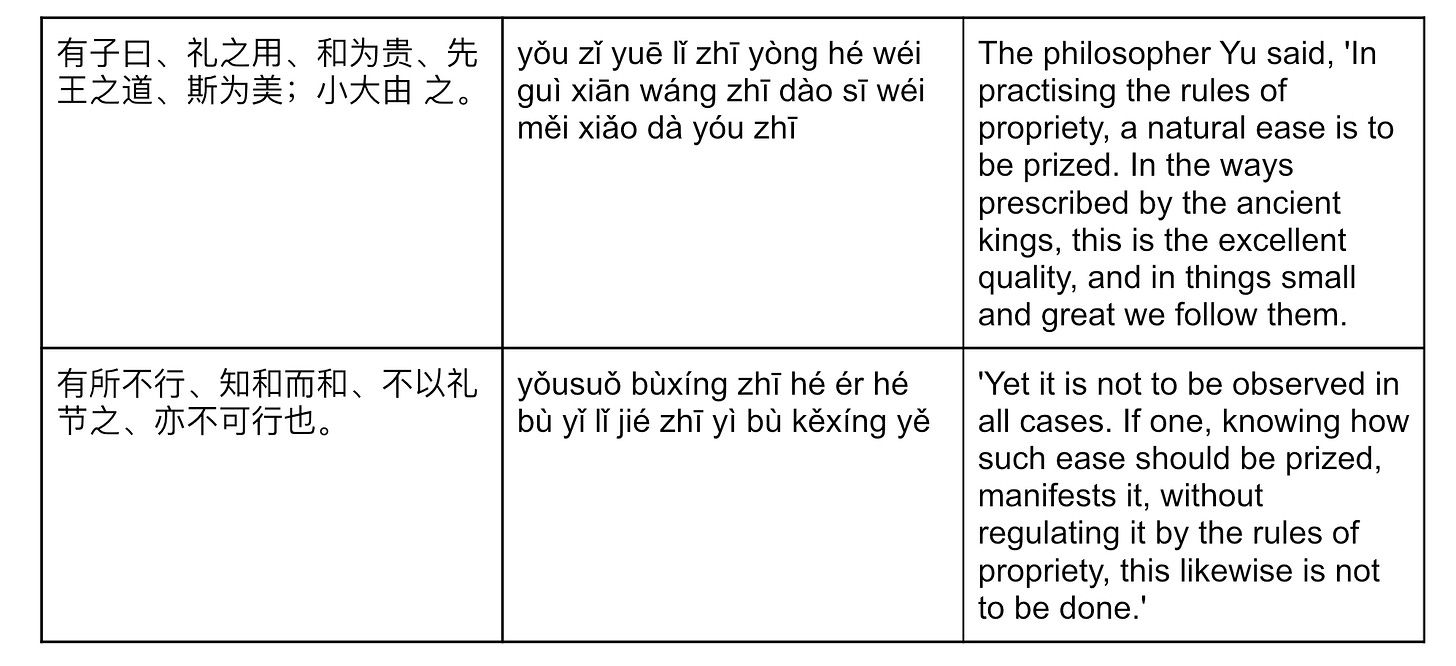

Saying 12

Speakers:

Youzi (有子) aka You Ruo (有若). A disciple of Confucius known for his love of history.

Words To Know:

和: He. Harmony.

先: Xian. First, Ancestral, Ancient

王: Wang. King.

道: Dao.

小大: Xiao Da. “small [and] big”, i.e. everything

不: Bu. No, not, can not.

Commentary:

So, it’s come to this. Both sayings today are from someone other than Confucius, namely a certain You Ruo (有若). As is typical, this man is strongly highlighted in the introduction books (three quotes!) and mentioned in the outer books (12.9) but makes no appearance in what I call the inner books.

Both this saying and the next discuss lesser virtues, things that are good to practice but not even sufficient to be a Junzi (君子). In particular, this saying is about He (和), harmony.

The character 和 is a pair of simple radicals. The radical 禾 means grain and the radical 口 means mouth. The radical 禾 is mainly phonetic in character - the Chinese words for rice and harmony are homophones in Old Chinese, Mandarin and Cantonese.

I think He (和) originally referred to the musical instrument which was the precursor to the sheng (笙) and the hulusi (葫芦丝) - that is, a small free reed aerophone. There certainly was an instrument of this name. The He (和) instrument would play the harmony behind a flute. The characteristic Chinese flute - the Di (笛) - with its Di Mo (笛膜), a wrinkled membrane, is not much older than Confucius. The characteristic buzzing sounds of these instruments gave and give the music a great deal of penetrative power even in suboptimal acoustic environments.

Anyway, with this interpretation, Youzi (有子)’s statement can be understood as a pun. It is the harmonies - not the melodies - that made the music of the ancient kings superior. Thus it is harmony that makes their way superior.

In so-called ‘Confucianism’ generally, He (和) is accorded a lesser status: - it isn’t even being introduced by Confucius but by a random disciple. This can be compared to its status as a major virtue in so-called ‘Daoism’. In the Laozi (老子), later called the Dao De Jing (道德經) or the “Way/Power Classic”, we find these words:

“知和曰常,知常曰明,益生曰祥。心使氣曰強。”

Which Legge translates

“To him by whom this harmony is known,

(The secret of) the unchanging (Dao) is shown,

And in the knowledge wisdom finds its throne.

All life-increasing arts to evil turn;

Where the mind makes the vital breath to burn,

(False) is the strength, (and o'er it we should mourn.)”

Just before this, Laozi (老子) says that the one thick in virtue is like an infant: “終日號而不嗄,和之至也。”, which can be freely translated “All day long he screams without becoming hoarse, so harmonious is his form.”. Thousands of years later, Nietzsche’s Zarathrustra would famously and similarly proclaim that the greatest transformation of Geist was into a child:

“Aber sagt, meine Brüder, was vermag noch das Kind, das auch der Löwe nicht vermochte? Was muss der raubende Löwe auch noch zum Kinde werden?

Unschuld ist das Kind und Vergessen, ein Neubeginnen, ein Spiel, ein aus sich rollendes Rad, eine erste Bewegung, ein heiliges Ja-sagen.”

But unlike Laozi (老子), Nietzsche doesn’t see the child as screaming without becoming hoarse. On the harmonious islands (glückseligen Inseln), Zarathustra proclaims:

“Dass der Schaffende selber das Kind sei, das neu geboren werde, dazu muss er auch die Gebärerin sein wollen und der Schmerz der Gebärerin.”

The child cries because the child has a want, a want to become the creative being , “der Schaffende”, that they are capable of being. So like Youzi (有子), Nietzsche sees harmony as a virtue but not the supreme and sufficient virtue.

Before moving on, I want to highlight a particularly fun part: “知和而和”, pronounced in Mandarin Chinese “zhī hé ér hé”. Literally “knowing harmony and harmony”, Legge translates this as “knowing how such ease should be prized” and Slingerland translates this as “know[ing] enough to value harmonious ease”.

Saying 13

Speakers:

Youzi (有子) aka You Ruo (有若). A disciple of Confucius known for his love of history.

Words to know:

近: Jin. Near, close.

信: Xin. Belief, trust, fatih.

恭: Gong. Respect.

不: Bu. Not, can not, no.

Commentary:

Look, I don’t have a great command of Chinese. But frankly, I don’t agree with Legge’s translation of “信近於义” (xin jin yu yi) as “agreements … made according to what is right” at all. Slingerland has “Trustworthiness comes close to righteousness” and Watson has “Trustworthiness is close to rightness”.

The recurring Jin (近) is not respected.This makes the last part - which pointedly lacks a Jin (近) - lose its impact. The logical structure making these two sayings form a unit is also tossed. Incidentally, 近 has a nice construction. The outer radical 辶, as we saw previously, to walk. The inner radical 斤 is a pictograph of an ax, a common image in Chinese characters to represent a person. Basically “I walk by” becomes “to be near”. Not very philosophical but instructive.

One more issue with Legge before moving on. There is a Bu (不) right there but Legge makes the sentence totally positive in his translation. This last sentence is flagged by Burton Watson as difficult to understand precisely and Legge seems to be trying to smooth over the careful hemming of Youzi (有子).

Anyway, both this and the previous analect are by a lesser speaker, Youzi (有子), on lesser virtues. In the last one, He (和) - harmony. In this one Xin (信) and Gong (恭) - Trustworthiness and Respect. These are good but not sufficient for social harmony. Let’s go into these characters as well. The character 信 is simply 人 (a stick figure, a person) squished next to 言 (a mouth with a moving tongue, words). To be your words, to speak the truth, to be trustworthy. Meanwhile, 恭 is a pair of hands offering an object over a heart. Respect is giving from the heart.

Let’s choose one of these to discuss today as there will be time to go over lesser virtues. I will choose Xin (信) for the very deep and important reason of being mentioned first. Choosing a hexagram from what was then called the the Zhou Yi (周易) and is now called the Yi Jing (易經) or “I Ching” at random, we find something interesting at Dui (兌), which David Hinton translates “Opening” and Richard John Lynn “Joy”. The second line is a yang or unbroken line says

“和兌之吉,行未疑也。”

Which Richard John Lynn translates “The good fortune that comes to one who achieves Joy through sincerity is due to the fact that he keeps his will trustworthy.”. Perhaps “undoubtable” would be a better translation of Wei Yi (未疑) than “trustworthy”. I say this mostly to have an excuse for one of the cutest etymologies, that of 疑: doubt, suspicion or confusion. It is an ideogram of a man with a cane looking around in slackjawed confusion. Treating the Yi Jing (易經) merely as a philosophical style guide, this ideogram helps us understand the concept of Xin (信). To be one’s words, to be trustworthy, is to not cause confusion.

Wang Bi helpfully adds the reason for this potential confusion: this yang (unbroken) line is in a yin (broken) position. If this line were changed to yin, then one would have swamp over thunder, Sui (隨). That yin, being female, is said to tie herself to the boy and abandon the mature man (in Richard John Lynn’s translation) and the third yin above her is said to tie herself to the mature man and abandon the boy (these males being other lines in the hexagram). This provides an interesting connection to Nietzsche and Laozi (老子) above.