Lun Yu 1.10 & 1.11

The First Dialog!

Chapter 1

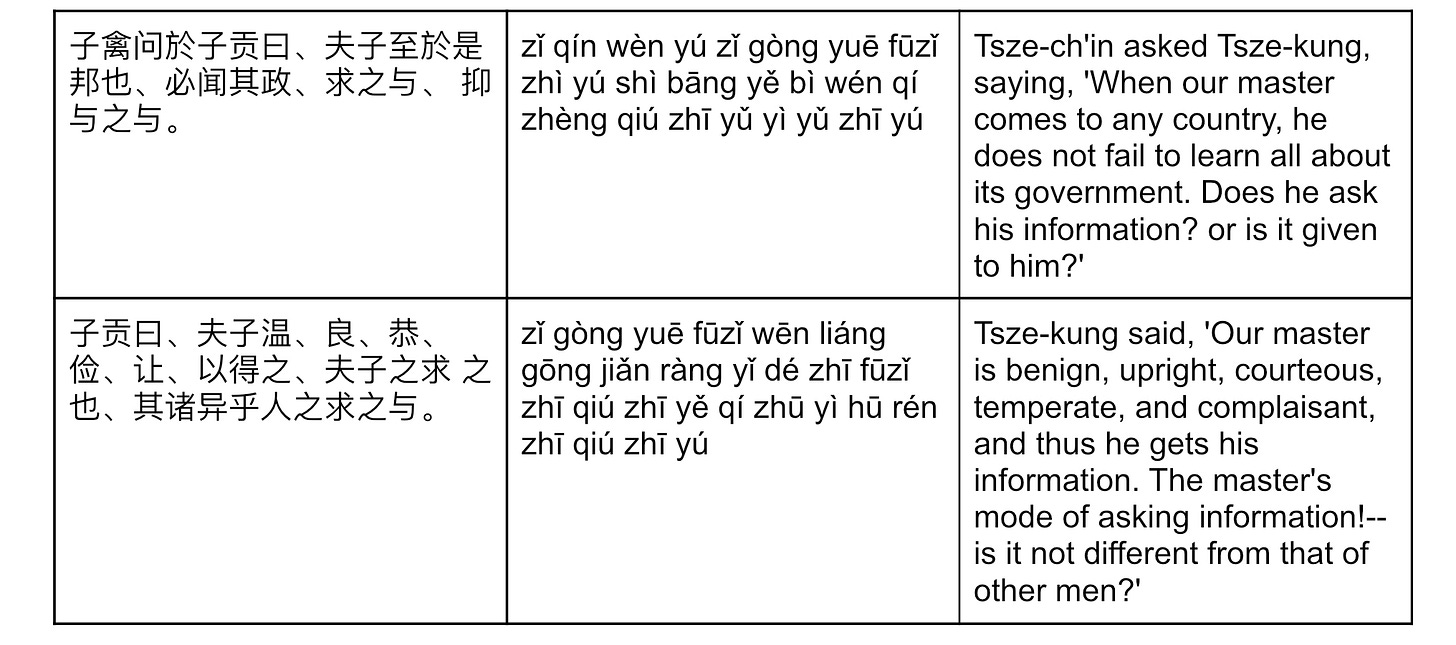

Saying 10

Speakers:

Ziqin (子禽), a minor disciple. Personal name: Chen Kang (陳亢)

Zigong (子贡), personal name Duanmu Ci (端木赐). A wealthy businessman who became one of the main disciples.

Words To Know:

Zi (之) - to go

Yu (与) - to give

Commentary:

The questioner, Ziqin (子禽), has a title indicates that he ran a school. All his questions (which are only in outer books such as this one) will be about education, including this one.

Benjamin Franklin in his Autobiography famously defined “Humility” as “[The imitation of] Jesus and Socrates.”. Earlier in the same book, he describes a crucial phase in his intellectual development as follows:

“While I was intent on improving my language, I met with an English grammar (I think it was Greenwood's), at the end of which there were two little sketches of the arts of rhetoric and logic, the latter finishing with a specimen of a dispute in the Socratic method; and soon after I procur'd Xenophon's Memorable Things of Socrates, wherein there are many instances of the same method. I was charm'd with it, adopted it, dropt my abrupt contradiction and positive argumentation, and put on the humble inquirer and doubter.”

Socrates method can be illustrated by the following quote from a translation of The Memorabilia, which is section III

“At another time he fell in with a man who had been chosen general and minister of war, and thus accosted him.

Soc. Why did Homer, think you, designate Agamemnon "shepherd of the peoples"? (1) Was it possibly to show that, even as a shepherd must care for his sheep and see that they are safe and have all things needful, and that the objects of their rearing be secured, so also must a general take care that his soldiers are safe and have their supplies, and attain the objects of their soldiering? Which last is that they may get the mastery of their enemies, and so add to their own good fortune and happiness; or tell me, what made him praise Agamemnon, saying: “He is both a good king and a warrior bold!”? Did he mean, perhaps, to imply that he would be a 'warrior bold,' not merely in standing alone and bravely battling against the foe, but as inspiring the whole of his host with like prowess; and by a 'good king,' not merely one who should stand forth gallantly to protect his own life, but who should be the source of happiness to all over whom he reigns? Since a man is not chosen king in order to take heed to himself, albeit nobly, but that those who chose him may attain to happiness through him. And why do men go soldiering except to ameliorate existence? (3) and to this end they choose their generals that they may find in them guides to the goal in question. He, then, who undertakes that office is bound to procure for those who choose him the thing they seek for. And indeed it were not easy to find any nobler ambition than this, or aught ignobler than its opposite.

After such sort [Socrates] handled the question: what is the virtue of a good leader? and by shredding off all superficial qualities, laid bare as the kernel of the matter that it is the function of every leader to make those happy whom he may be called upon to lead. ”

Thus Slingerland quotes Huang Kan’s opinion that Confucius could instantly know the way things are by being attentive to the common people. The good fortune of the ordinary people is the essence of effective leadership, not court intrigue. As we will see later, this proved a difficult opinion to maintain.

Poetically, this is a very dynamic saying, full of coming and going and giving. What tripped me up is that the word Shi (是) in this analect seems to be used in an unusual way. Shi (是) is the copular verb and the affirmative response in Chinese, so it is very, very common. However, I don’t think it is used in that way in this analect!

Looking it up, I found that in Ancient Chinese, Shi (是) meant not only the “right” in “That’s right” but also the right in “human rights”, as in “laws and customs”. Then Shi Bang (是邦) means “ways of the state”. This is a use that I haven’t encountered before.

Perhaps is helpful to take apart the character 是, which is a phono-semantic compound of 早 and 止. 早 has kind of a strange history. The original character was an acorn over thorns, but at some point (possibly near Confucius’s lifetime) it was reinterpreted as the sun over an armored man. The character for armor can also be used to mean first. Whatever the signs making up the characters are, it is used to mean “morning” or generally “before now”. The other part, 止 is a three-toed animal foo, often used to mean “stopping point” or “end”. The overall impression is that of stopping where you start, especially with the second interpretation of 早.

We can look at a couple uses in the good ol’ I Ching (易经). Hexagram 11, Tai (泰), has a typical use of Shi (是). Richard John Lynn translates Tai (泰) as “Peace”. The presentation begins

“泰,小往大來,吉亨。則是天地交,而萬物通也;上下交,而其志同也。”

Legge translates this as

“'The little come and the great gone in Tai, and its indication that there will be good fortune with progress and success' show to us heaven and earth in communication with each other, and all things in consequence having free course, and (also) the high and the low, (superiors and inferiors), in communication with one another, and possessed by the same aim.”

The first sentence is just the image quoted exactly. The second sentence is a discourse on the dynamics of Tiandi (天地) – heaven and earth – during the time of Tai (泰). Wang Bi helpfully explains (as translated by Richard John Lynn) “What is called Tai refers to the time when things go smoothly on a grand scale. When what is above and what is below achieve interaction on such a grand scale, things lose their proper place and time.”. So Tai (泰) is peace in the sense of the calm before the storm, the period when the contradictions are all nicely put asleep under the blanket of ideology. One can see even Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis in Tai (泰): the very success of a financial environment spells its doom.

Coming back to Shi (是), Richard John Lynn translates “則是” simply as “that is,”, which is more accurate but less poetic than Legge’s “show to us”. Still, you can clearly see that the language of Ziqin (子禽) is pretty far from the Hexagram. With all this said, if I have misinterpreted Shi (是) in this analect I would love to know.

Saying 11

Speakers:

Kongzi (孔子), i.e. Confucius

Words To Know:

Fu (父) - father

Zhi (志) - intentions

Xing (行) - to go, to work, to be able to to be good in the sense of functionally. Originally “to walk”.

Commentary:

This is one of Kongzi’s (孔子) many comments on moral psychology. Judging a person fit or unfit was Confucius’s dayjob for most of his life. In the state of Lu he was minister of justice. When he was elderly - as he is here - he was a state elder, a Yuan Lao (元老), who would be overseeing the appointment of officials. He felt very strongly about the importance of a bureaucracy independent of the feudal warrior-aristocrats and made piecemeal improvements in his lifetime in the various states in which he lived.

The emphasis here is the continuity between Zhi (志) and Xing (行): intention and action. When judging a young person, one bases judgements on intentions because the young person’s actions are restrained by their parents. Contrariwise, when judging an adult, one looks towards conduct. The famous analect 2.10 will emphasize that it is impossible for an adult to conceal their moral character.

Xing (行) was originally a word which meant “to walk”, so one could read Guan Qi Xing “观其行” as “watch how he walks” or even more poetically “watch the path on which he walks”. This reading connects the judgment of the adult to that of the Dao (道): does the adult continue to clear the footpath or does he indolently allow it to become overgrown?

The San Nian (三年), three years, that Confucius talks about is the traditional period of mourning - the Ding You (丁忧) - after the death of a parent. The mourning was to be “into the third year”, that is 25 months. Confucius understands this as repayment to the late parent for the 25 months of complete dependence that begins human life. I once saw an argument for an origin which was much more complicated but believable. The mourning period was originally a one year mourning period for a mother. The father was given a double period plus one month (Chinese ritual required odd numbers for funeral related actions) as part of the Zhou dynasty reforms. Powerful mothers were occasionally given the same treatment as fathers, which eventually became the norm.

The Li Ji (礼记) or Book Of Rites, states

“事親有隱而無犯,左右就養無方,服勤至死,致喪三年。”

Which Rebecca Robinson in “Ritual and Sincerity in Early Chinese Mourning Rituals” translates as

“In serving his parents, a son should conceal (their faults) and remonstrate with them. In every way he should look after them without definite rules, should serve them to the utmost until their death, and then wear the three-years mourning for them to the fullest.”

As Robinson points out, mere formality was allowed in all mourning rituals except that of the parents. This is an issue as the San Nian (三年) ritual was quite debilitating. Not only did one have to live on a dirt floor in a grass hut eating meager amounts of grain and congee, but also contact with the family was severely restricted. The heaviest burden of mourning fell onto the inheriting son (often called “the eldest” in both Chinese and Western sources, and he often was, vaguely).

Perhaps this explains why Confucius seems to have placed enormous weight on the mourning ritual as a sign that the mourner was not a selfish person. Perhaps what Confucius observed was whether a young lord was required to logroll the moment his father died. This would be a sign of a weak state where the path is left unbeaten.