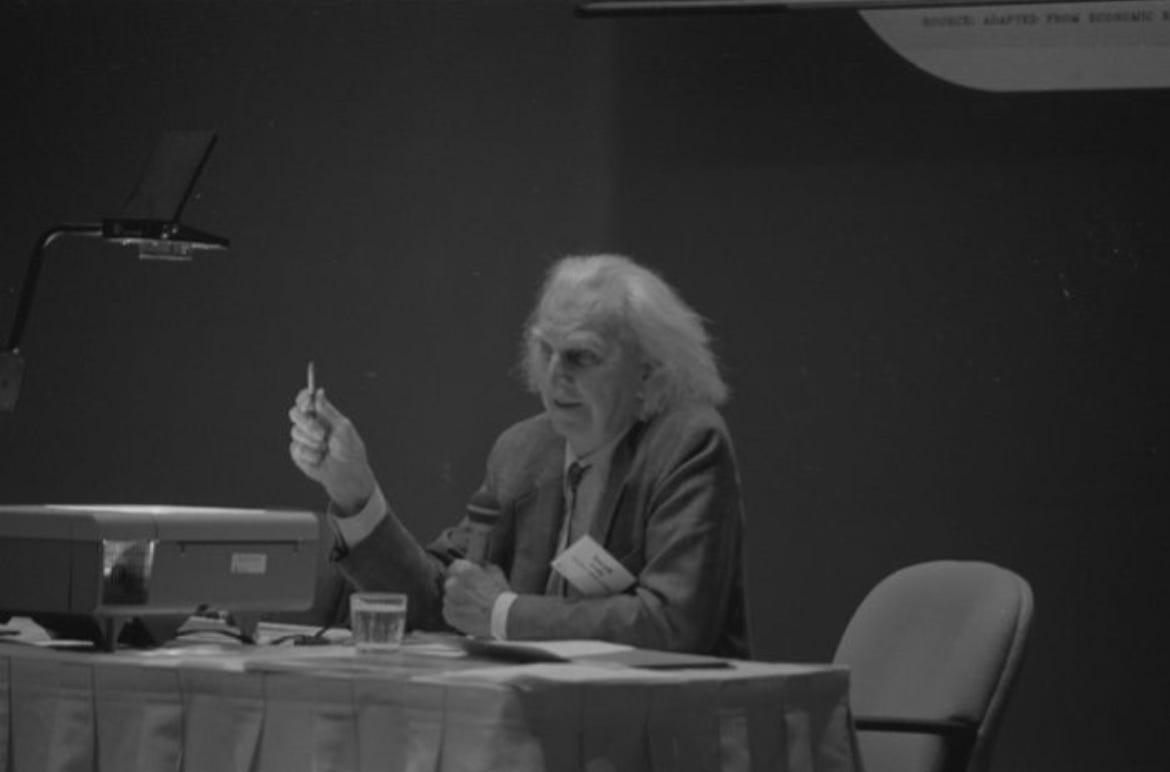

Getting To Know Kenneth Boulding

Papers, Please

It’s Ken Boulding Month At CVAR!

Now, uh, what does that mean? Who the heck was Ken Boulding? Why does it matter? Well, I’ll give just enough of a biography to get to his peak period, and the reason it matters should become obvious, given certain assumptions about the readership here.

Economist Ken Boulding was born in Liverpool to Methodist parents in 1910. He was eight years old when WWI ended and his father got the right to vote. Boulding went to Oxford on a chemistry scholarship in 1928, just in time to escape The Great Depression.

In the early 20s, the revolution headed by Einstein and Bohr meant the world’s problems looked essentially chemical. By 1929, they did not. In fact, the head of the chemistry department at Oxford - Frederick Soddy - had openly abandoned chemistry, and by the time Boulding arrived was mostly giving lectures on what he called “Cartesian Economics”. Soddy’s ideas were about what you’d expect from an intelligent chemist doing economics in 1928: lots of worrying about debt, a generous helping of Malthusianism, some vague appeals to thermodynamics and attempts to warn people of the threat of Peak Coal.

Of course, there’s no evidence that Boulding had ever even heard of Soddy’s ideas – Soddy is only mentioned by reputation in his autobiographical articles – but they give a sense of the intellectual world into which Boulding stepped. Whatever the case may be, Boulding began studying economics in the summer of 1930, reading Marshall and Marx in the midst of the utter collapse of industrial society. After seeing Keynes lecture in November 1930, he became a convinced Keynesian six years before the General Theory!. Boulding published his first paper - an attempt to precisely delimit the case in which displacement cost had a clear meaning and validity - in 1931 and moved to Chicago in 1932.

At the University Of Chicago, Boulding found an environment that was far more appealing than the sea of starched shirts of Oxford. Particularly appealing to the young Boulding were the pugnacious but scrupulously honest and unpretentious Frank Knight and the mathematical whiz Henry Schultz (then mentoring a teenage Herbert Simon). The excitement of a semester at Harvard with the quick witted dandy Joseph Schumpeter was, however, dulled by Boulding’s father’s sudden death (he was hit by a drunk driver).

Soon after, Boulding’s scholarship required him to return to England. He fortunately got a job in the midst of the depression at the University Of Edinburgh, a menial job in a stuffy social environment. Though miserable, Boulding befriended and learned accounting from William Thriepland Baxter, who, as the man with the most apt name for the title, would later become the first accounting professor in England.

In 1935, Knight’s article attacking Boulding’s work on Capital Theory (capital theory attempts to isolate the causes of interest rates) put Boulding back on the map as someone people are talking about more and more. He moved back to America as soon as he could. Though he bounced from school to school - Colgate, Fisk, Iowa State, Michigan, Boulder - Boulding maintained a high level (both in quality and volume) of scholarly output.

Kenneth Boulding’s first book - Economic Analysis, an introductory textbook - was published in 1941 as he taught at Iowa State. This was the first textbook to incorporate Keynesian thinking, six years before Lorie Tarshis’s Elements. Were I to pick out Boulding’s peak period, it would likely be 1941 through 1956, after which he buys a dictation machine and his writing loses a fair bit of tightness. In this period he develops his most distinctive views and the papers from that era form the core of today’s selection.

There is a lot more to say about Boulding’s life and thoughts, but we won’t hear about it until the full article comes out later this month. Today, the point is to see him for yourself. I will recommend six papers - three above the line and three below. The above-the-paywall papers will all be from the peak period and will be what I think Boulding has to offer general economics discourse. The below the line section will have more material for specialists.

Introducing Kenneth Boulding

A Liquidity Preference Theory Of Market Prices

If you’re going to read just one Ken Boulding paper, make it this one!

This paper exchanges the traditional Supply And Demand theory of the causes of Price And Quantity for a Price And Quantity theory of Supply And Demand. The starting point is that both sides of an exchange are giving up a commodity - one a general commodity and the other money. This means that the balance sheets of both sides change. Boulding introduces a crucial and powerful simplification of the firm’s decision making: the firm targets a “liquidity ratio”. If, for instance, this ratio is the same for all dealers, then the money price is proportional to the ratio of the stocks of money and the commodity, with the constant of proportionality a simple function of the liquidity ratio. In essence, liquidity preference doesn’t just determine the gross interest rate, but in fact determines all prices.

This paper, like much of Boulding’s work and indeed life, is simultaneously revolutionary and conservative. It is conservative in its use of Marshallian tools to the revolutionary end of a new classification of the causes of price and does so in a way that essentially recapitulates the core of Keynes’ General Theory.

Implications For General Economics Of More Realistic Theories Of The Firm

This is a more “literary” article aimed at a general econ-literate audience about how the firm should be thought of in economics after the development of the monopolistic competition approach.

Ever since Marshall, there have been prayers that economics would eventually incorporate the tree of the firm in addition to the forest of the market. The difficulty is simple: the internal structure of the firm has little directly to do with the comparative statics of price and quantity, as was put forcefully by Knight, and so it is basically impossible to use the tools of economics to reach determinate conclusions about firm behavior. Boulding here tries to create a space for that prayer, which is needed if it will ever be answered.

The power of Boulding’s system come in many ways from combining the insights of these two papers. They provide the seed for a Firm & Market based rather than Supply & Demand based view of economic life in the small.

The Concept Of Need For Health Services

Another “literary” article, this one aimed at non-economists.

To a first approximation the actor A ‘needs’ a service B if and only if A receiving B is a necessary condition for A to maintain homeostasis. In principle, need is far more precise and observable than demand, but Boulding points out the concept of homeostasis applied to organisms with intrinsic life-cycles (and creative agency!) requires clarification.

It’s articles like this that originally attracted me to Boulding and Paul Samuelson. There is a feeling in these types that methodology can free rather than restrict. Where Stigler’s theory doesn’t already have ‘need,’ he denies ‘need’ exists without the slightest argument. Methodology in Stigler’s work is a straightjacket. Boulding sees ‘need’ as a new challenge, which has a complex relationship to want. Teasing out this relation may require actual thought, but the methodology is much more freeing.

Three More Technical Ken Boulding Papers

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Continuous Variation to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.